Majora's Mask - Breaking the Cycle (Minor Spoilers)

Posted 12/4/21

One of the most important pillars of Majora’s Mask’s game design is the three-day cycle. It’s a divisive mechanic that either makes or breaks the game for most

people: you either love the time management aspects or you’re too pressured. Despite the challenges of this time limit, the benefits of the mechanic vastly outweigh

the cons. The strongest factor at play is the change from a static world like previous titles in the series to a dynamic one. Every Zelda title leading up to and

after Majoras’s Mask focuses on a linear Hero’s Journey. The hero always answers a call to action after a traumatic event that projects him on a path to saving the

world in a fairytale-esque story, and that’s led to the mass appeal of the series. Every game’s story can easily be told as a “legend” or as a bedtime story you

tell your kids about the hero saving the world. I can’t say Majora’s Mask doesn’t follow the formula of saving the world, but it twists the formula in a creative

way to make something truly special: it normalizes the idea of success through failure.

The land of Termina’s fate is written plainly in its name in that the moon will crash to the ground in 3 days time. This ends the game and destroys everything. With

bustling towns, regions, and dungeons to explore in the four corners of the map, there is simply too much for Link to do in such a short time span. Soon after

starting the game, you acquire the power to go back in time to the start of the first day. However, you’ll lose all of your quest progress and items, save for

select key items. Even after your 4th or 5th cycle trying to set the world right, you probably still won’t have accomplished everything you need to. It is because

the player is allowed to fail and the world is allowed to be destroyed that Majora’s Mask’s worldbuilding and characters can soar to new heights for the series.

The land of Termina’s fate is written plainly in its name in that the moon will crash to the ground in 3 days time. This ends the game and destroys everything. With

bustling towns, regions, and dungeons to explore in the four corners of the map, there is simply too much for Link to do in such a short time span. Soon after

starting the game, you acquire the power to go back in time to the start of the first day. However, you’ll lose all of your quest progress and items, save for

select key items. Even after your 4th or 5th cycle trying to set the world right, you probably still won’t have accomplished everything you need to. It is because

the player is allowed to fail and the world is allowed to be destroyed that Majora’s Mask’s worldbuilding and characters can soar to new heights for the series.

Previous games saw Ganon as the world’s villain where he sought to enslave and conquer, and even then it was always accomplished in a very PG sense. The player rarely

witnesses any acts of horror, just the typical fantasy villain fanfare of making the world dark and spawning monsters everywhere. The moon in Majora’s Mask, besides

being visually unsettling, seeks to destroy. There are no vague threats here or evil castles with mustache-twirling scoundrels. The moon will fall in exactly 72 hours

every cycle and kill everyone in the world.

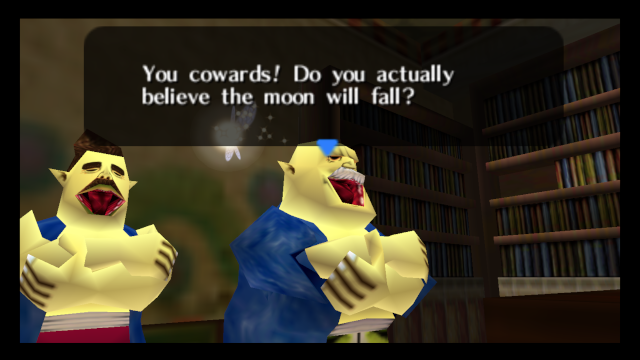

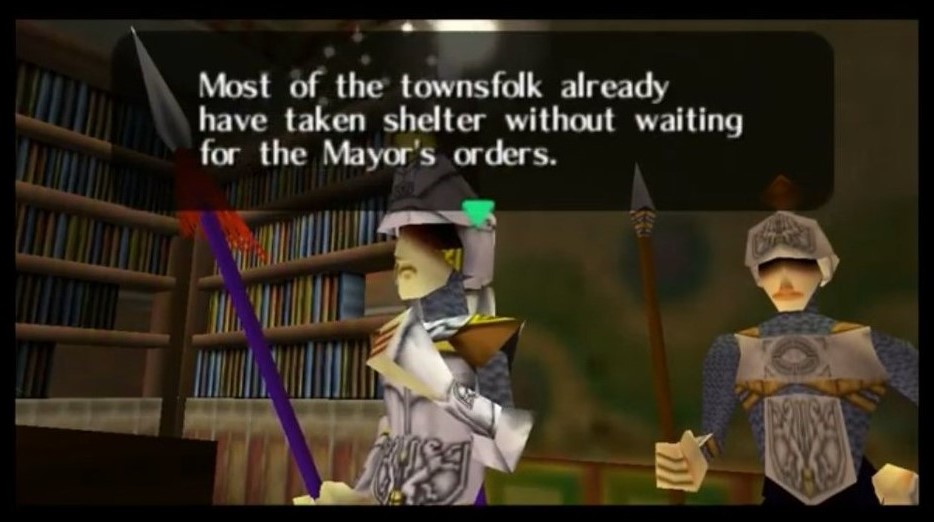

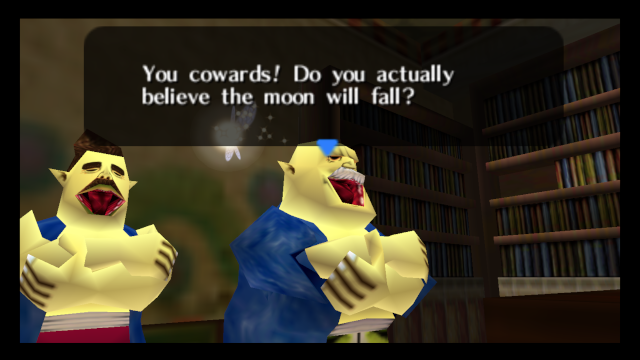

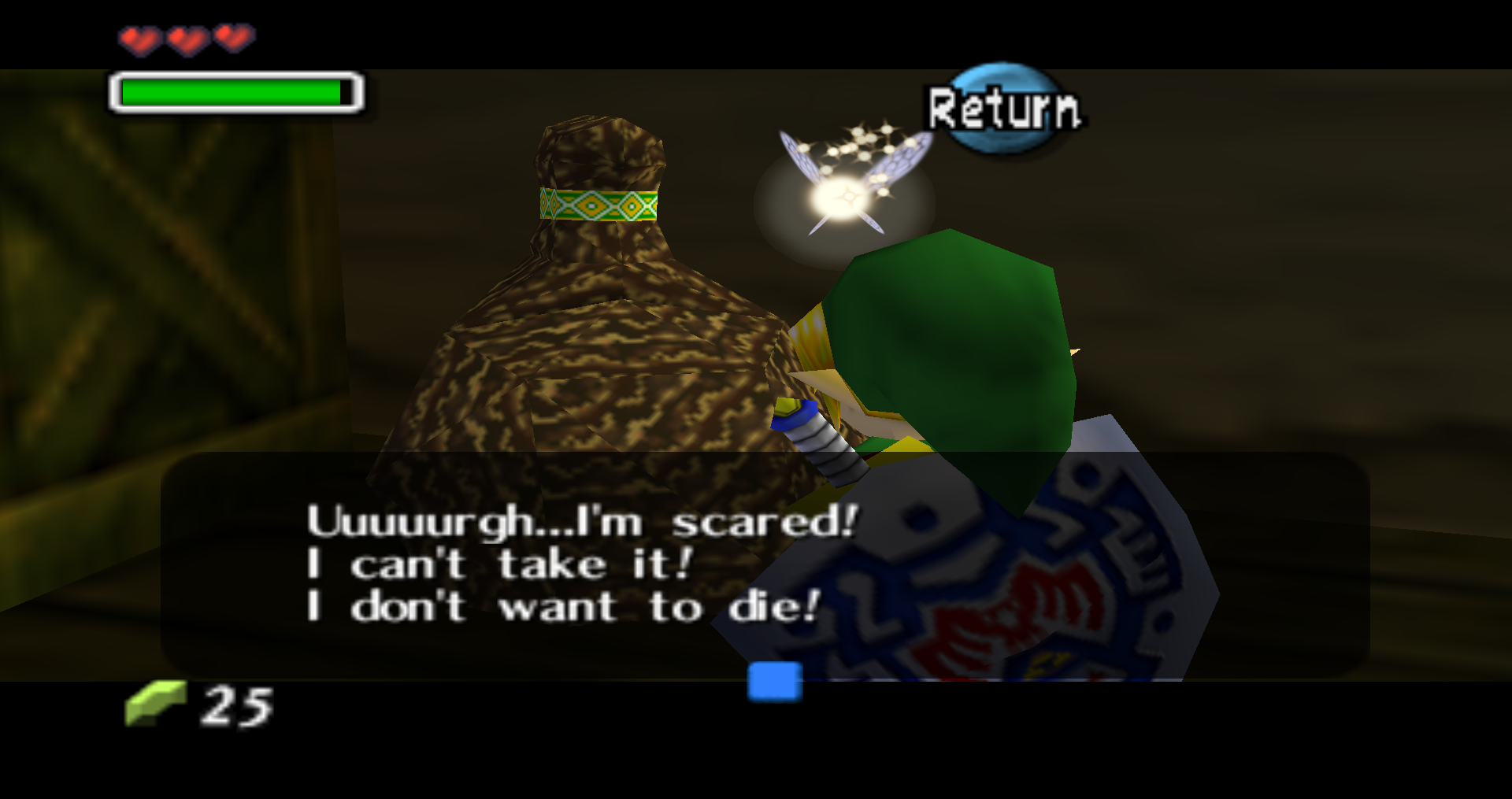

As the moon gets closer and closer with each passing day, characters react to their impending doom in intricate and satisfying ways. Everyone has something different

to say if you catch them at just the right time in just the right place. The Clock Town mayor’s office provides the best example of the divide in opinion on the

encroaching threat from above. Mayor Dotour hosts an emergency meeting between the town guard and the carpenters. The town’s annual Carnival of Time is conveniently

scheduled to be held in 3 days time. The Town Guard Captain, Viscen, pleads with Dotour to cancel the carnival and give the order to evacuate the citizens to safety.

The Head Carpenter, Mutoh, snaps back that the moon won’t actually fall and that the carnival is a tradition that must go on. Unable to make a decision, Mayor

Dotour mulls over thoughts of his family as he retreats from the debate. People’s reactions to the end of the world range from lighthearted to grim as they struggle

with how to handle what could be their last days to live. Some immediately make plans to leave town, others remain to look for lost friends and relatives. Some

resign themselves to their fate for duty or for love, others scoff at the idea of the moon falling until the final hours when they cower in fear.

As the moon gets closer and closer with each passing day, characters react to their impending doom in intricate and satisfying ways. Everyone has something different

to say if you catch them at just the right time in just the right place. The Clock Town mayor’s office provides the best example of the divide in opinion on the

encroaching threat from above. Mayor Dotour hosts an emergency meeting between the town guard and the carpenters. The town’s annual Carnival of Time is conveniently

scheduled to be held in 3 days time. The Town Guard Captain, Viscen, pleads with Dotour to cancel the carnival and give the order to evacuate the citizens to safety.

The Head Carpenter, Mutoh, snaps back that the moon won’t actually fall and that the carnival is a tradition that must go on. Unable to make a decision, Mayor

Dotour mulls over thoughts of his family as he retreats from the debate. People’s reactions to the end of the world range from lighthearted to grim as they struggle

with how to handle what could be their last days to live. Some immediately make plans to leave town, others remain to look for lost friends and relatives. Some

resign themselves to their fate for duty or for love, others scoff at the idea of the moon falling until the final hours when they cower in fear.

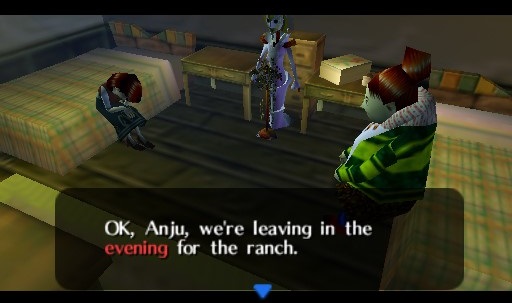

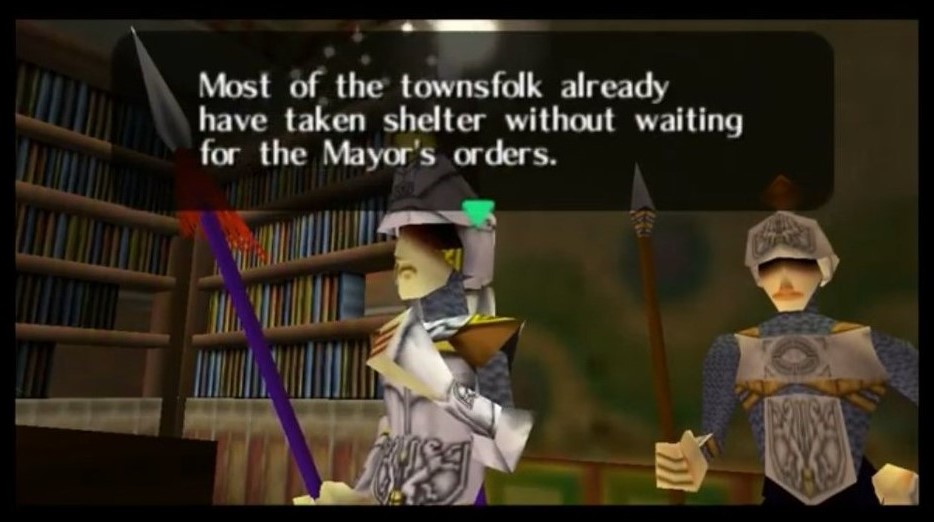

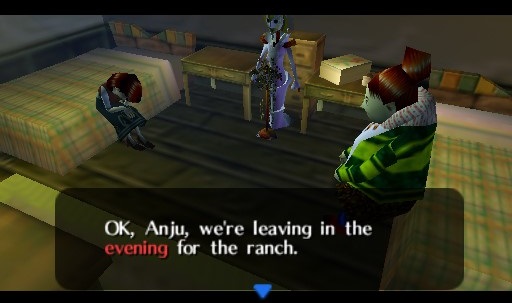

There’s a high level of polish in the game that makes these characters and interactions so meaningful if you invest the time and effort to care. Clock Town’s music

changes from merry and melodic, to a softer prance as a downpour begins on the second day, to fast-paced with darker undertones as the final day carries on. As the

last hours tick away, a somber and haunting melody plays. Mutoh the carpenter, abandoned by his subordinates fleeing to safety, confidently scoffs at the crimson

sky, calling his men cowards and beginning the carnival for a near ghost town. Cremia at the nearby ranch gives her kid sister Romani her first taste of alcohol in

an attempt to dull her senses before their untimely demise. Anju, one of the StockPot Inn’s owners, ignores her family’s desperate pleas to flee and waits alone in

a room on the second floor, holding out hope her missing betrothed will find her so they may face the dawn, or their death, together. With no orders to evacuate,

the town guards remain at the gates for the remaining populace, quivering as they stare up at the incoming moon with a hand at their heart and the other clenching

their pikes.

There’s a high level of polish in the game that makes these characters and interactions so meaningful if you invest the time and effort to care. Clock Town’s music

changes from merry and melodic, to a softer prance as a downpour begins on the second day, to fast-paced with darker undertones as the final day carries on. As the

last hours tick away, a somber and haunting melody plays. Mutoh the carpenter, abandoned by his subordinates fleeing to safety, confidently scoffs at the crimson

sky, calling his men cowards and beginning the carnival for a near ghost town. Cremia at the nearby ranch gives her kid sister Romani her first taste of alcohol in

an attempt to dull her senses before their untimely demise. Anju, one of the StockPot Inn’s owners, ignores her family’s desperate pleas to flee and waits alone in

a room on the second floor, holding out hope her missing betrothed will find her so they may face the dawn, or their death, together. With no orders to evacuate,

the town guards remain at the gates for the remaining populace, quivering as they stare up at the incoming moon with a hand at their heart and the other clenching

their pikes.

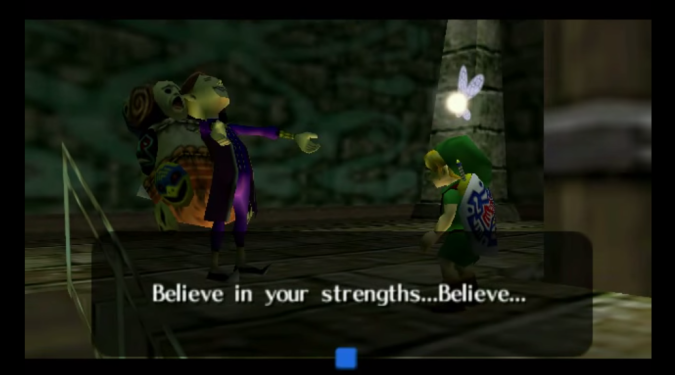

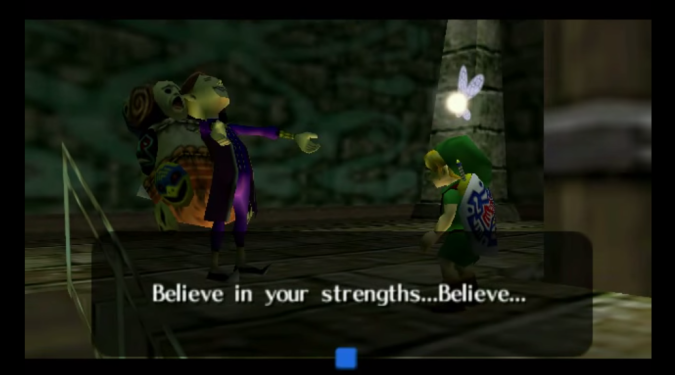

All the while, the Happy Mask Salesman counts away the hours each day inside the ever-ticking Clock Tower. If you’ve played Ocarina of Time before, you’ll notice

that nearly every NPC in this game is reused from there, albeit their names and personalities are vastly different for the narrative’s benefit. The Happy Mask

Salesman is no exception, except he adds deeper meaning to Link’s journey. The brooding land of Termina is an alternate reality from the green fields and blue

skies of Hyrule where Link travelled from. In a world where Link is a stranger to everyone, the Happy Mask Salesman is the lone person who knows Link from Hyrule.

His memory is lost like everyone else when Link resets time, but he nonetheless professes his belief that Link will achieve his goals. It’s as though he knows the

power Link holds over time and has no worries. Whether you subscribe to the belief that Link resets time for everyone or abandons everyone else to a doomed timeline,

the Happy Mask Salesman is always confident he will succeed eventually.

All the while, the Happy Mask Salesman counts away the hours each day inside the ever-ticking Clock Tower. If you’ve played Ocarina of Time before, you’ll notice

that nearly every NPC in this game is reused from there, albeit their names and personalities are vastly different for the narrative’s benefit. The Happy Mask

Salesman is no exception, except he adds deeper meaning to Link’s journey. The brooding land of Termina is an alternate reality from the green fields and blue

skies of Hyrule where Link travelled from. In a world where Link is a stranger to everyone, the Happy Mask Salesman is the lone person who knows Link from Hyrule.

His memory is lost like everyone else when Link resets time, but he nonetheless professes his belief that Link will achieve his goals. It’s as though he knows the

power Link holds over time and has no worries. Whether you subscribe to the belief that Link resets time for everyone or abandons everyone else to a doomed timeline,

the Happy Mask Salesman is always confident he will succeed eventually.

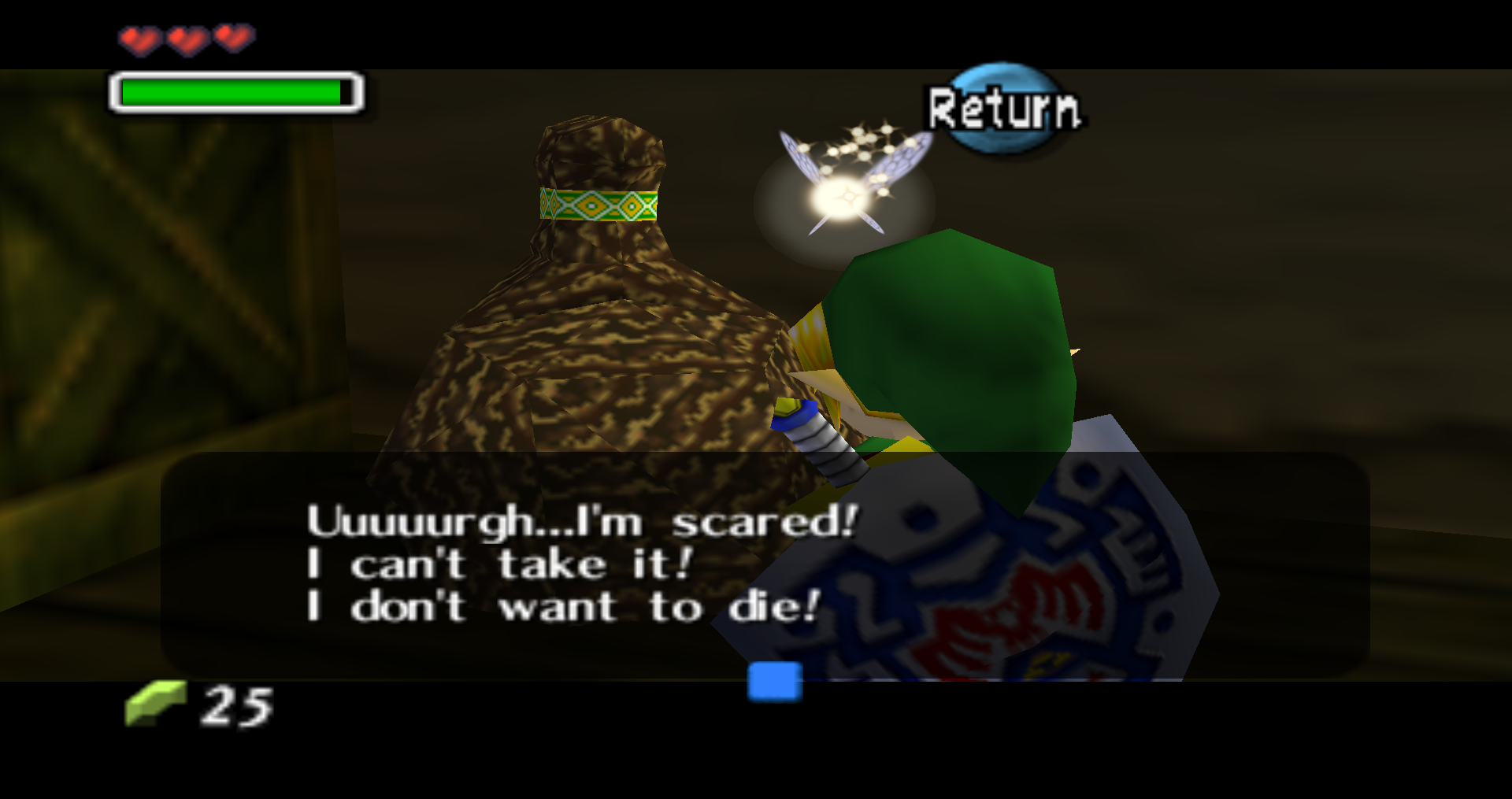

Characters exhibit a great amount of depth and nuance as Link repeats the 3-day cycle again and again. You understand their jobs, their relationships, their dreams,

and their regrets. You manage to finish a dungeon, but miss critical character events by mere hours. You use information gathered from previous cycles of failure in

the hopes you’ll get them a happy ending this time. You may be able to reset the cycle or restart the game for that matter, but for these people every second counts.

Every interaction causes a ripple effect with unforeseen consequences. Your actions on day one can lead to deciding who stays in town or who flees by the final day,

or who faces their doom without regrets aside those who panic.

Characters exhibit a great amount of depth and nuance as Link repeats the 3-day cycle again and again. You understand their jobs, their relationships, their dreams,

and their regrets. You manage to finish a dungeon, but miss critical character events by mere hours. You use information gathered from previous cycles of failure in

the hopes you’ll get them a happy ending this time. You may be able to reset the cycle or restart the game for that matter, but for these people every second counts.

Every interaction causes a ripple effect with unforeseen consequences. Your actions on day one can lead to deciding who stays in town or who flees by the final day,

or who faces their doom without regrets aside those who panic.

There’s great irony in how Majora’s Mask exhibits a better mechanical and immersive payoff with how it utilizes time compared to its predecessor, Ocarina of Time.

Ocarina focuses more on the grand adventure and how the world can change after 7 years. The problem is what I mentioned in the beginning, the world of Ocarina is

static. Most characters interact with the world by standing in a predetermined spot or doing laps around a village with their one-and-done line of info for the

player. There’s some character quests the player can follow that add depth and connections to a few, but only so much as to make them one-dimensional in nature.

The 7 year time leap also fails to drastically alter the situation of most characters in a meaningful way. You can count on your hand how many characters visibly

age up after the time skip. The entirety of Hyrule Castle Town has been displaced to Kakariko Village, and most have their one line of info replaced by another

one-liner. Ocarina does a fantastic job focusing on the bigger picture of the Hero’s Journey while missing opportunities the timeskip provides towards worldbuilding

and character interactions. Majora’s Mask excels in this regard by condensing years of change into mere days. Instead of huge leaps of time, it analyzes days,

hours, and minutes to breathe life into characters and locales. You care about what people are doing when and where, and how you can make meaningful progress

in limited time. Deeper symbolism and lore exist for those who search for it, so much so that plenty of YouTube videos and articles like this one are out there

dissecting the world and crafting convincing and enjoyable fan theories.

There’s great irony in how Majora’s Mask exhibits a better mechanical and immersive payoff with how it utilizes time compared to its predecessor, Ocarina of Time.

Ocarina focuses more on the grand adventure and how the world can change after 7 years. The problem is what I mentioned in the beginning, the world of Ocarina is

static. Most characters interact with the world by standing in a predetermined spot or doing laps around a village with their one-and-done line of info for the

player. There’s some character quests the player can follow that add depth and connections to a few, but only so much as to make them one-dimensional in nature.

The 7 year time leap also fails to drastically alter the situation of most characters in a meaningful way. You can count on your hand how many characters visibly

age up after the time skip. The entirety of Hyrule Castle Town has been displaced to Kakariko Village, and most have their one line of info replaced by another

one-liner. Ocarina does a fantastic job focusing on the bigger picture of the Hero’s Journey while missing opportunities the timeskip provides towards worldbuilding

and character interactions. Majora’s Mask excels in this regard by condensing years of change into mere days. Instead of huge leaps of time, it analyzes days,

hours, and minutes to breathe life into characters and locales. You care about what people are doing when and where, and how you can make meaningful progress

in limited time. Deeper symbolism and lore exist for those who search for it, so much so that plenty of YouTube videos and articles like this one are out there

dissecting the world and crafting convincing and enjoyable fan theories.

Majora’s Mask was developed in just under two years, yet it stands as a testament to how creative humans can get when they’re pressed for time. The deadlines for the

developers directly translates to the time constraints of the game. The smaller dungeon count from previous games is counteracted by the emphasis on designing meaning

in the people and places you interact with. Time is simultaneously an infinite resource for the player, and a finite luxury for the people of Termina. Everything melds

together to form a timeless classic that you’ll remember long after the credits roll.

Majora’s Mask was developed in just under two years, yet it stands as a testament to how creative humans can get when they’re pressed for time. The deadlines for the

developers directly translates to the time constraints of the game. The smaller dungeon count from previous games is counteracted by the emphasis on designing meaning

in the people and places you interact with. Time is simultaneously an infinite resource for the player, and a finite luxury for the people of Termina. Everything melds

together to form a timeless classic that you’ll remember long after the credits roll.

NieR Automata - Chaotic Harmony Through Gameplay and Narrative (Spoilers)

Posted 10/5/20

NieR: Automata is perhaps one of the strangest games to release in the last decade. Officially, the game is classified in the action-adventure genre, but there are

a variety of mechanics present in the game that make it impossible to define it solely as such. Many games that attempt to combine several different mechanics and

genres fail to give the player a coherent and enjoyable experience, yet NieR manages to do so gracefully. Apart from creating an fluid play experience, the

developers of NieR, Platinum Games, set out to build an intriguing world that players could explore and understand through a variety of means. By no means is the

world of NieR a simple one to comprehend either; it is best described as a web of complexity that will reward those players who think critically about the narrative

through an existential crisis of sorts. However, NieR: Automata, through its immersive narrative and varied gameplay mechanics, is extraordinary in that it offers

an experience that makes the player question their own morals, and even their own humanity. The combination of various genres and mechanics to tell a complex, but

enjoyable story is what makes NieR: Automata a must-play experience.

One of the most important elements of the action-adventure genre is combat, and NieR executes this very well. NieR’s combat system is one of the most unique systems

I have come across in the past few years. Platinum Games is known for their previous works like Bayonetta where combat is a stylish artform that is just as fluid

on-screen as it is simple to learn as it is complex to master. NieR is no exception to this as you can choose from a variety of swords, lances, guns, and hammers

to wield, and even engage in hand-to-hand combat if you wish. The characters 2B and A2 can use two weapons at once to unleash devastating combos, while the

character 9S can hack into enemy robots to play quick 2D minigames for some interesting results. Player’s are also equipped with a flying Pod unit that provides tactical

assistance through blaster fire, conjuring swords, gravity wells, heat-seeking missiles, and many more combinations. The game’s combat is phenomenally well-done in that anyone can

pick up the controls in a few minutes and mash buttons to their hearts content to perform satisfying combos, while those seeking depth will find the weapon variety

and expanded combat options to their liking.

One of the most important elements of the action-adventure genre is combat, and NieR executes this very well. NieR’s combat system is one of the most unique systems

I have come across in the past few years. Platinum Games is known for their previous works like Bayonetta where combat is a stylish artform that is just as fluid

on-screen as it is simple to learn as it is complex to master. NieR is no exception to this as you can choose from a variety of swords, lances, guns, and hammers

to wield, and even engage in hand-to-hand combat if you wish. The characters 2B and A2 can use two weapons at once to unleash devastating combos, while the

character 9S can hack into enemy robots to play quick 2D minigames for some interesting results. Player’s are also equipped with a flying Pod unit that provides tactical

assistance through blaster fire, conjuring swords, gravity wells, heat-seeking missiles, and many more combinations. The game’s combat is phenomenally well-done in that anyone can

pick up the controls in a few minutes and mash buttons to their hearts content to perform satisfying combos, while those seeking depth will find the weapon variety

and expanded combat options to their liking.

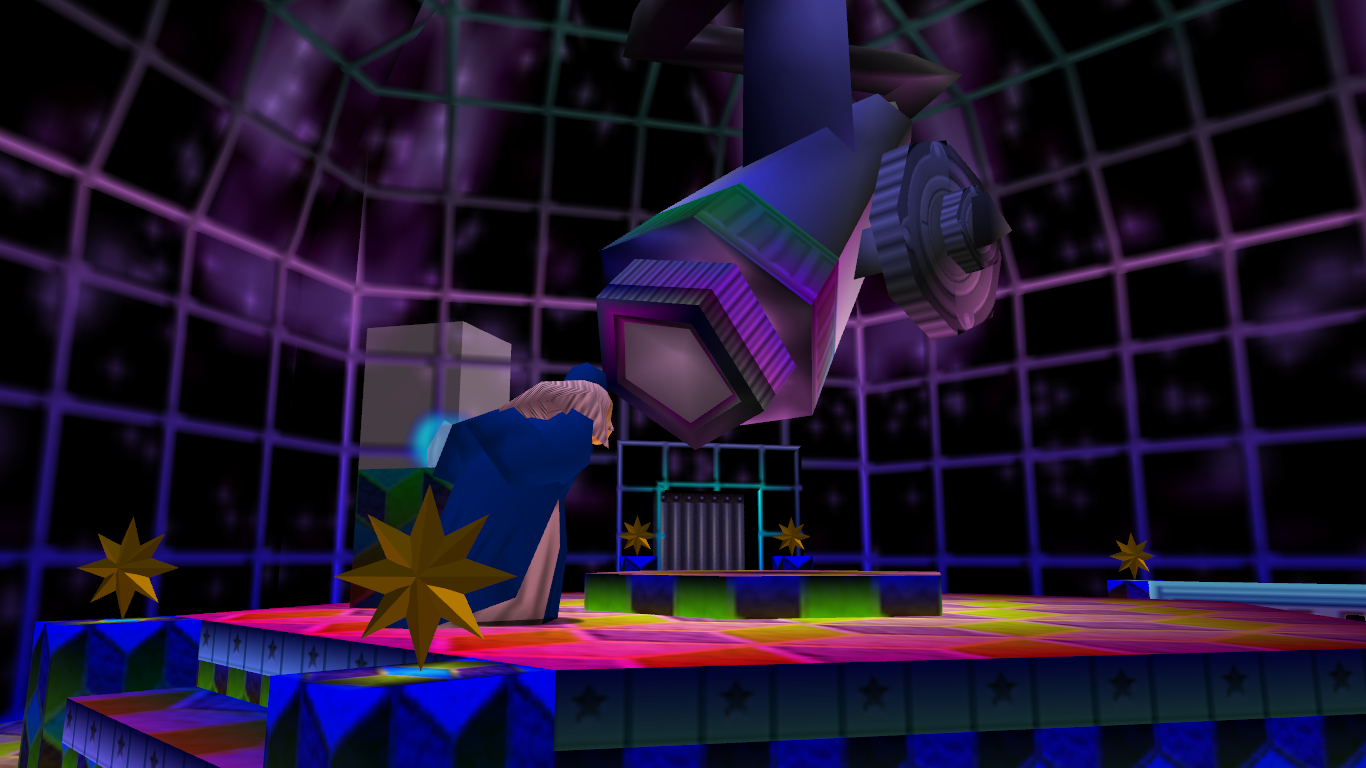

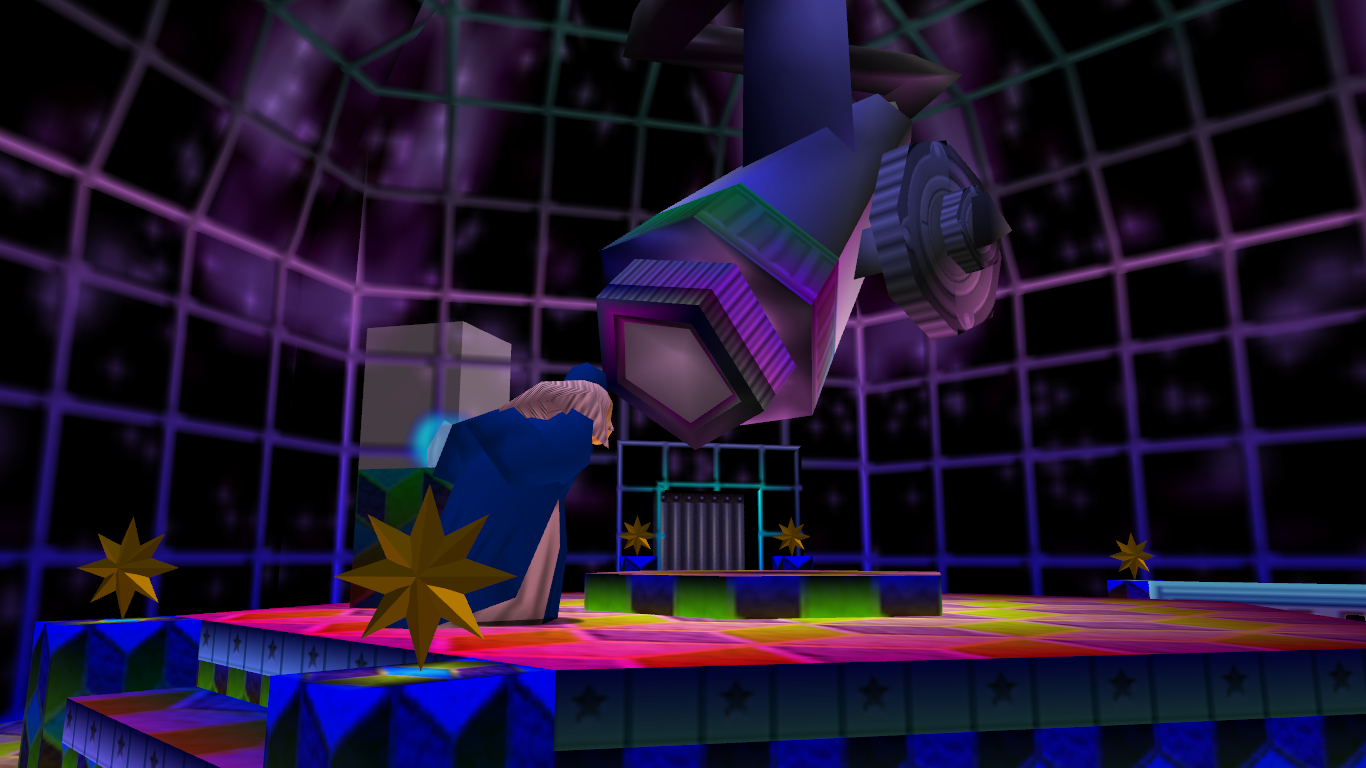

Combat doesn’t just take the form of third-person action though. The game constantly keeps you on your feet by switching up the camera angle to the viewpoint of a

2D side scroller, an over-the-top panorama, and even a frantic bullet hell. These camera changes can drastically change the gameplay when you’re flying around in

a giant mech, or traversing a long bridge filled with enemies on either side of you. The game never uses this mechanic as a gimmick to the point of exhaustion and

over-use; instead it keeps you engaged in the space around you and adds levels of depth to otherwise mediocre locales. For example, an ancient and run-down castle

is turned into a 2D side scroller reminiscent of classic Castlevania-esque games, and enemies pop out from either side of you as well as the foreground and

background to challenge your perception of the level.

Combat doesn’t just take the form of third-person action though. The game constantly keeps you on your feet by switching up the camera angle to the viewpoint of a

2D side scroller, an over-the-top panorama, and even a frantic bullet hell. These camera changes can drastically change the gameplay when you’re flying around in

a giant mech, or traversing a long bridge filled with enemies on either side of you. The game never uses this mechanic as a gimmick to the point of exhaustion and

over-use; instead it keeps you engaged in the space around you and adds levels of depth to otherwise mediocre locales. For example, an ancient and run-down castle

is turned into a 2D side scroller reminiscent of classic Castlevania-esque games, and enemies pop out from either side of you as well as the foreground and

background to challenge your perception of the level.

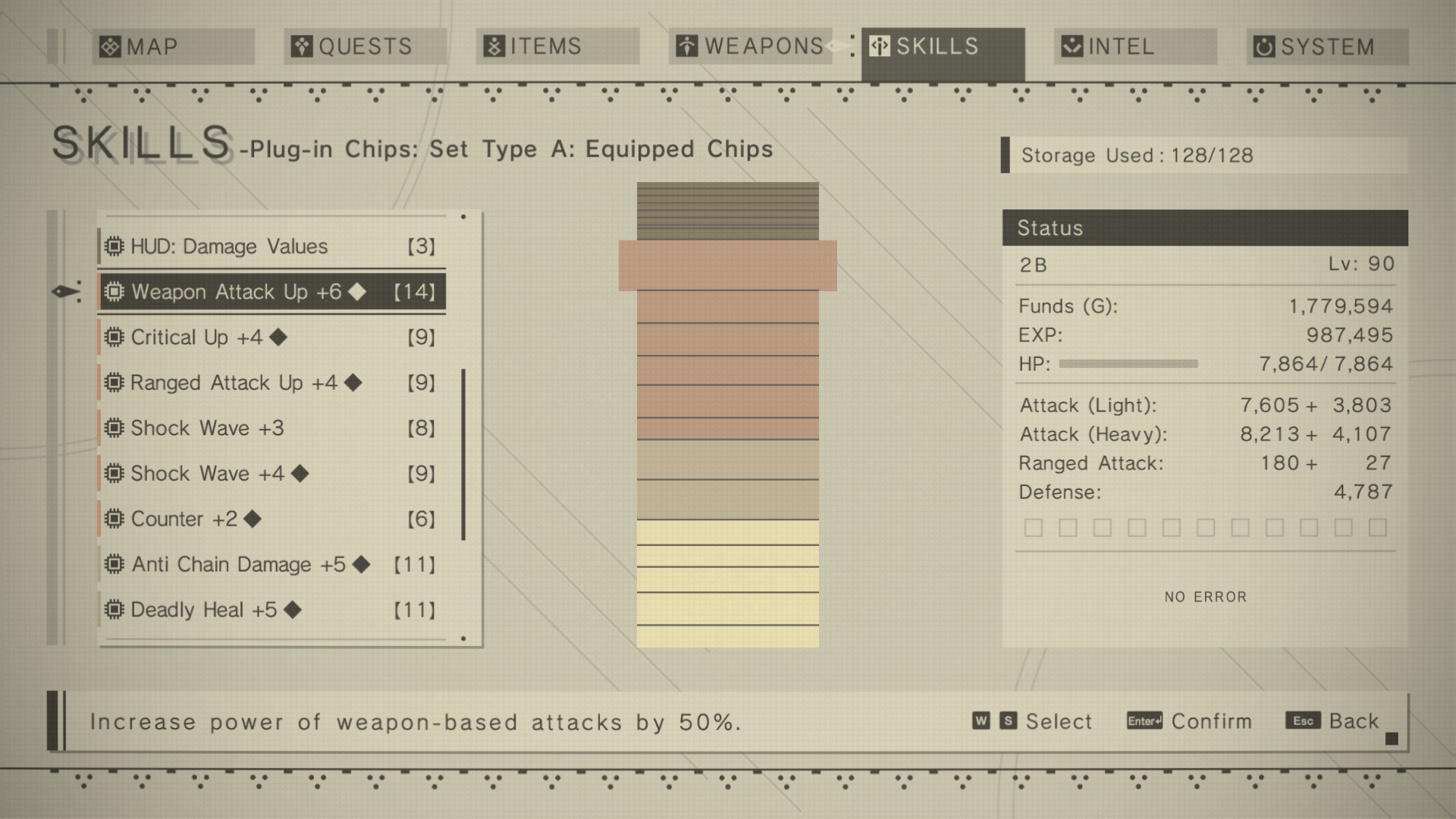

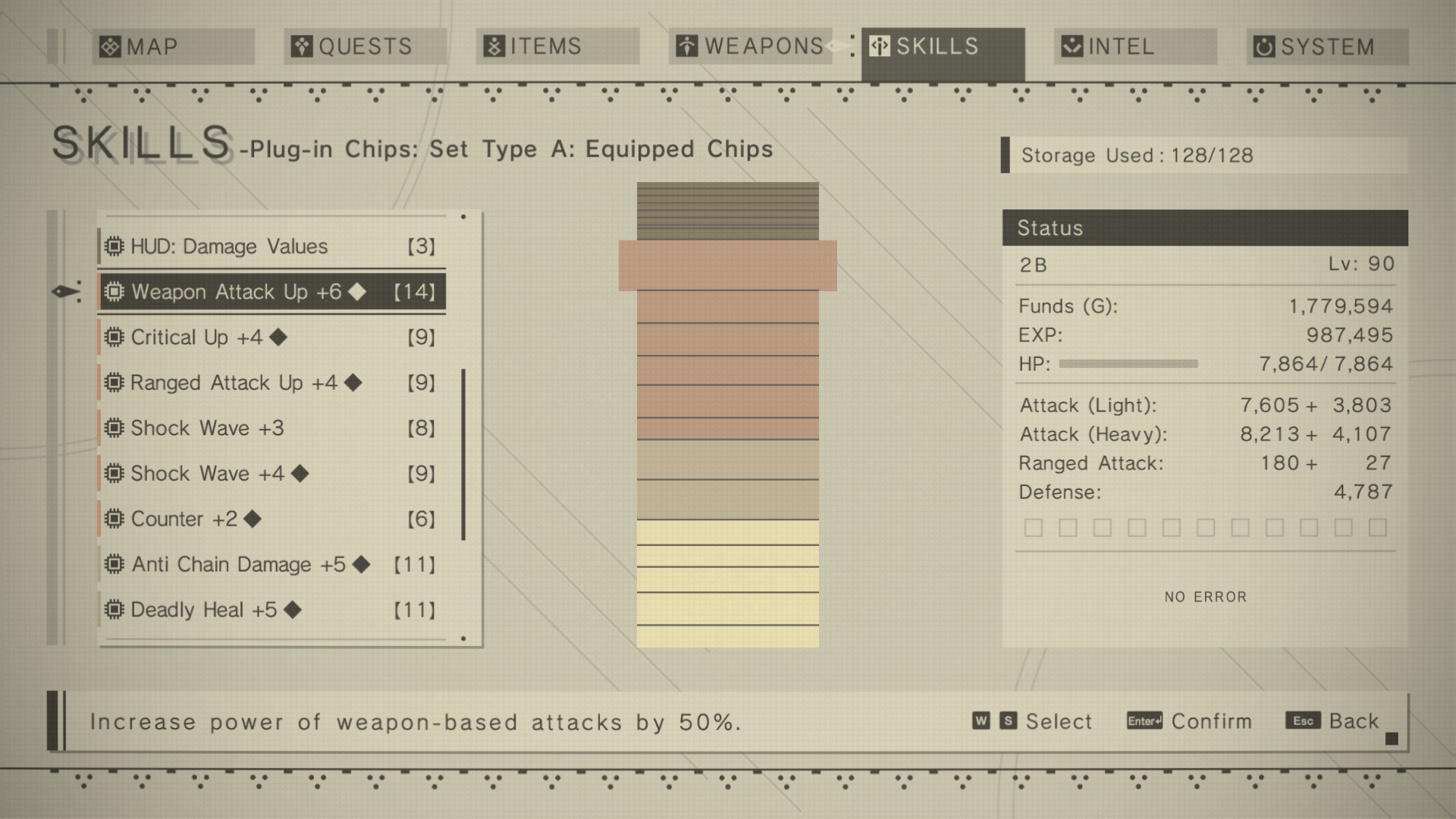

One of the most immersive aspects of NieR is its intricate RPG system. Throughout the game, you play as humanoid-androids, and the RPG system does an excellent job

of making you feel like you’re playing as an android. In place of a traditional skill tree, you collect computer chips during your travels and can use these chips

to add additional functionality to your gameplay, such as enhancing your combat capabilities or boosting your defense. Additionally, players will find that every

element of their HUD is itself a chip that can be added or removed at will. Considering you can only have a set number of chips active at a time, this ability to

fundamentally change every aspect of your play experience is incredible. Adding to this, there is even a chip that represents the android’s operating system, which

when removed will kill the player. There are many different items and chips in the game that one would not normally expect from this genre where mostly every mechanic

is designed to help you succeed. Some of these chips simply make your health bar or minimap disappear, while others seem counter-productive such as the OS chip.

Why would the developer allow the player the ability to kill themselves in this way? The simple answer to this is, why not. In her work “Hamlet on the Holodeck,”

Janet Murray talks about player agency and how computer games can offer plenty of satisfaction when there is a direct correlation between player choices and

consequences. NieR’s RPG mechanics add a level of depth to player customization that many other games in the genre simply force-feed you. By giving the player these

options, NieR breaks down the barrier between the player and the player’s character in unexpected and unique ways that create a meaningful experience every time you

play.

One of the most immersive aspects of NieR is its intricate RPG system. Throughout the game, you play as humanoid-androids, and the RPG system does an excellent job

of making you feel like you’re playing as an android. In place of a traditional skill tree, you collect computer chips during your travels and can use these chips

to add additional functionality to your gameplay, such as enhancing your combat capabilities or boosting your defense. Additionally, players will find that every

element of their HUD is itself a chip that can be added or removed at will. Considering you can only have a set number of chips active at a time, this ability to

fundamentally change every aspect of your play experience is incredible. Adding to this, there is even a chip that represents the android’s operating system, which

when removed will kill the player. There are many different items and chips in the game that one would not normally expect from this genre where mostly every mechanic

is designed to help you succeed. Some of these chips simply make your health bar or minimap disappear, while others seem counter-productive such as the OS chip.

Why would the developer allow the player the ability to kill themselves in this way? The simple answer to this is, why not. In her work “Hamlet on the Holodeck,”

Janet Murray talks about player agency and how computer games can offer plenty of satisfaction when there is a direct correlation between player choices and

consequences. NieR’s RPG mechanics add a level of depth to player customization that many other games in the genre simply force-feed you. By giving the player these

options, NieR breaks down the barrier between the player and the player’s character in unexpected and unique ways that create a meaningful experience every time you

play.

When I say, “every time you play,” I truly mean each time you play through the game. NieR’s story is told over the course of 4 separate playthroughs of the game.

Once you finish your first playthrough, you then replay the stories events from the perspective of a different character with slight differences. Unfortunately,

this change of perspective does not come without its flaws. While the first and third playthroughs are unique adventures, the second and fourth are mostly copies

of their predecessors. While they offer the player different combat options due to the character change, these playthroughs are otherwise mundane as you rush to the

finish to reach the next playthrough. Of course, those who enjoy NieR’s combat over the story may not have a problem with this, yet it is still a design flaw that

ruins the game’s narrative pacing to an extent. However, there is still some merit to be found in these playthroughs. Playing from the perspective of different

characters not only grants the player different combat options, but also allows them to see story events they wouldn’t otherwise. Furthermore, those who were once

partner characters that followed you around the first time around become much more relatable now that you must fight using their skillset and see the world through

their eyes. Even the hacking in the game allows you to fight as a machine using their own limited weapons and mobility. While replaying mostly similar experiences is

tedious, the differing narrative perspectives as well as the emotional investment you attain is well worth the extra time invested.

When I say, “every time you play,” I truly mean each time you play through the game. NieR’s story is told over the course of 4 separate playthroughs of the game.

Once you finish your first playthrough, you then replay the stories events from the perspective of a different character with slight differences. Unfortunately,

this change of perspective does not come without its flaws. While the first and third playthroughs are unique adventures, the second and fourth are mostly copies

of their predecessors. While they offer the player different combat options due to the character change, these playthroughs are otherwise mundane as you rush to the

finish to reach the next playthrough. Of course, those who enjoy NieR’s combat over the story may not have a problem with this, yet it is still a design flaw that

ruins the game’s narrative pacing to an extent. However, there is still some merit to be found in these playthroughs. Playing from the perspective of different

characters not only grants the player different combat options, but also allows them to see story events they wouldn’t otherwise. Furthermore, those who were once

partner characters that followed you around the first time around become much more relatable now that you must fight using their skillset and see the world through

their eyes. Even the hacking in the game allows you to fight as a machine using their own limited weapons and mobility. While replaying mostly similar experiences is

tedious, the differing narrative perspectives as well as the emotional investment you attain is well worth the extra time invested.

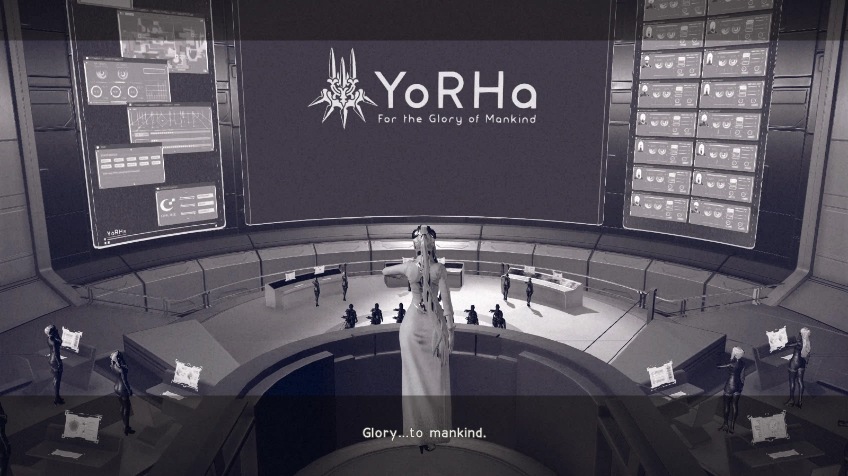

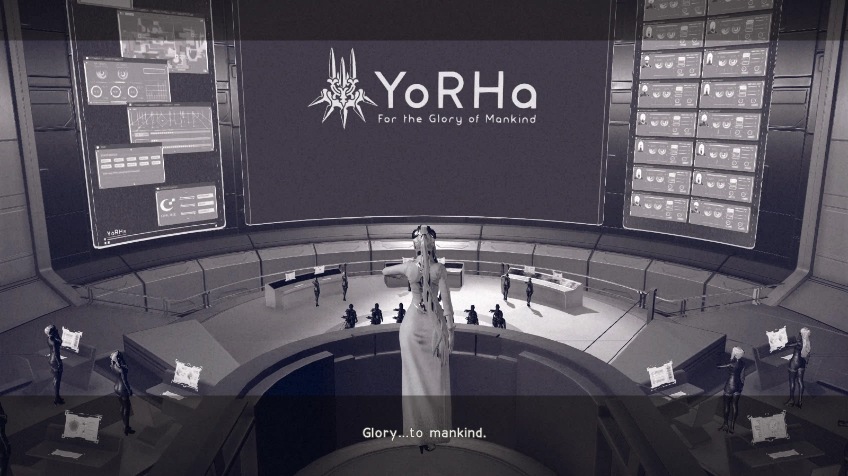

Finally, all of these mechanics tie together to the benefit of NieR’s narrative. The premise of the story is simple to grasp, albeit a bit bizarre. Long ago, alien lifeforms

invaded Earth and forced the human population to evacuate and recolonize on a distant planet. The humans vowed to reclaim Earth and established a base

of androids on the moon that would become humanity’s fighting force. Thousands of years later, you take control of the androids 2B, 9S, and A2 as they continue to

fight the Aliens’ machines on Earth in an effort to reclaim Earth for the humans. The androids’ motto is unsurprisingly “Glory to Mankind” as they receive annual

transmissions from the distant human population. At first, the player gets the sense they’re playing as deadly and efficient androids who are modelled after humans,

and that they are fighting to one day rejoin mankind. Throughout the journey, the androids attempt to justify their crusade against the machines, who are much more

similar in form to robots, by saying the machines are simply programmed to fight them and that they have no sense of consciousness. However, the player eventually

discovers that the humans had actually been annihilated long ago, and that these transmissions were simply staged to give the androids a sense of purpose. This

discovery is fundamental to the player’s understanding of the events around them and how they perceive the characters they interact with. On the one hand, the

androids the player is controlling subsequently have their dreams of seeing mankind again dashed. Their only purpose was to fight the machines for mankind’s salvation.

Yet, mankind’s extinction, and the lies they’ve been fed for so many years, ultimately defeats the purpose of the androids and they begin questioning their reasons for

continuing at all. Similarly, the player sees the machines in a parallel dilemma. You realize that the aliens died out long ago as well and the machines have had only

their prewritten programming to rely on for centuries. In the absence of a master of sorts, many of the machines have developed strange tendencies in their pursuit of

learning on Earth, such as wearing clothing, caring for animals, performing plays, and even attempting sexual intercourse with other machines.

Finally, all of these mechanics tie together to the benefit of NieR’s narrative. The premise of the story is simple to grasp, albeit a bit bizarre. Long ago, alien lifeforms

invaded Earth and forced the human population to evacuate and recolonize on a distant planet. The humans vowed to reclaim Earth and established a base

of androids on the moon that would become humanity’s fighting force. Thousands of years later, you take control of the androids 2B, 9S, and A2 as they continue to

fight the Aliens’ machines on Earth in an effort to reclaim Earth for the humans. The androids’ motto is unsurprisingly “Glory to Mankind” as they receive annual

transmissions from the distant human population. At first, the player gets the sense they’re playing as deadly and efficient androids who are modelled after humans,

and that they are fighting to one day rejoin mankind. Throughout the journey, the androids attempt to justify their crusade against the machines, who are much more

similar in form to robots, by saying the machines are simply programmed to fight them and that they have no sense of consciousness. However, the player eventually

discovers that the humans had actually been annihilated long ago, and that these transmissions were simply staged to give the androids a sense of purpose. This

discovery is fundamental to the player’s understanding of the events around them and how they perceive the characters they interact with. On the one hand, the

androids the player is controlling subsequently have their dreams of seeing mankind again dashed. Their only purpose was to fight the machines for mankind’s salvation.

Yet, mankind’s extinction, and the lies they’ve been fed for so many years, ultimately defeats the purpose of the androids and they begin questioning their reasons for

continuing at all. Similarly, the player sees the machines in a parallel dilemma. You realize that the aliens died out long ago as well and the machines have had only

their prewritten programming to rely on for centuries. In the absence of a master of sorts, many of the machines have developed strange tendencies in their pursuit of

learning on Earth, such as wearing clothing, caring for animals, performing plays, and even attempting sexual intercourse with other machines.

There are many peculiar experiences within NieR that I can go on describing, but ultimately I believe it is important to emphasize just how well NieR is

able to invest you into a world that is so foreign, and yet so relatable. Being able to experience the game multiple times over gives the player time and reason to

assert their own questions about the game and its characters. The androids claimed that they were vastly different from the robot-like machines, but is that really

true? The androids may have been modelled after humans and fought for “mankind,” but they were ultimately deceived in the end and lost their sole purpose for existing.

Arguably, the machines were closer to resembling mankind with their human-like actions and their quest for knowledge. Then again, there are moments of genuine love and

affection between androids as well. Ultimately, the player realizes that there are absolutely no humans in the universe of NieR and that they are playing as robots

fighting robots who follow a doctrine of 1’s and 0’s. Yet, each and every one of these robots has some aspect of them that makes them uniquely human.

There are many peculiar experiences within NieR that I can go on describing, but ultimately I believe it is important to emphasize just how well NieR is

able to invest you into a world that is so foreign, and yet so relatable. Being able to experience the game multiple times over gives the player time and reason to

assert their own questions about the game and its characters. The androids claimed that they were vastly different from the robot-like machines, but is that really

true? The androids may have been modelled after humans and fought for “mankind,” but they were ultimately deceived in the end and lost their sole purpose for existing.

Arguably, the machines were closer to resembling mankind with their human-like actions and their quest for knowledge. Then again, there are moments of genuine love and

affection between androids as well. Ultimately, the player realizes that there are absolutely no humans in the universe of NieR and that they are playing as robots

fighting robots who follow a doctrine of 1’s and 0’s. Yet, each and every one of these robots has some aspect of them that makes them uniquely human.

Ian Bogost talks about the timid nature of video games in his essay “Video Games are Better Without Stories” and how most games’ narratives could just be told through

film and television. NieR is a direct challenge to this idea in that it is only through the time spent playing as the characters and investing time in multiple

playthroughs that the player gains a more emotional investment in the game’s world. You might laugh at the machine that dresses up as a singer and sloppily puts

on makeup, but you eventually realize that that machine was trying to understand what love was as she sought the attention of another machine. She, if you’ve grown

to recognize a machine having gender, constantly sought perfection in her beauty and was met with unrequited love, and so you feel empathy for the machine as you destroy

her on your second playthrough. Was the machine foolish to believe she could learn how to love, or does her idea of perfecting her body to get attention

relate to a flaw in how we think in our society?

Ian Bogost talks about the timid nature of video games in his essay “Video Games are Better Without Stories” and how most games’ narratives could just be told through

film and television. NieR is a direct challenge to this idea in that it is only through the time spent playing as the characters and investing time in multiple

playthroughs that the player gains a more emotional investment in the game’s world. You might laugh at the machine that dresses up as a singer and sloppily puts

on makeup, but you eventually realize that that machine was trying to understand what love was as she sought the attention of another machine. She, if you’ve grown

to recognize a machine having gender, constantly sought perfection in her beauty and was met with unrequited love, and so you feel empathy for the machine as you destroy

her on your second playthrough. Was the machine foolish to believe she could learn how to love, or does her idea of perfecting her body to get attention

relate to a flaw in how we think in our society?

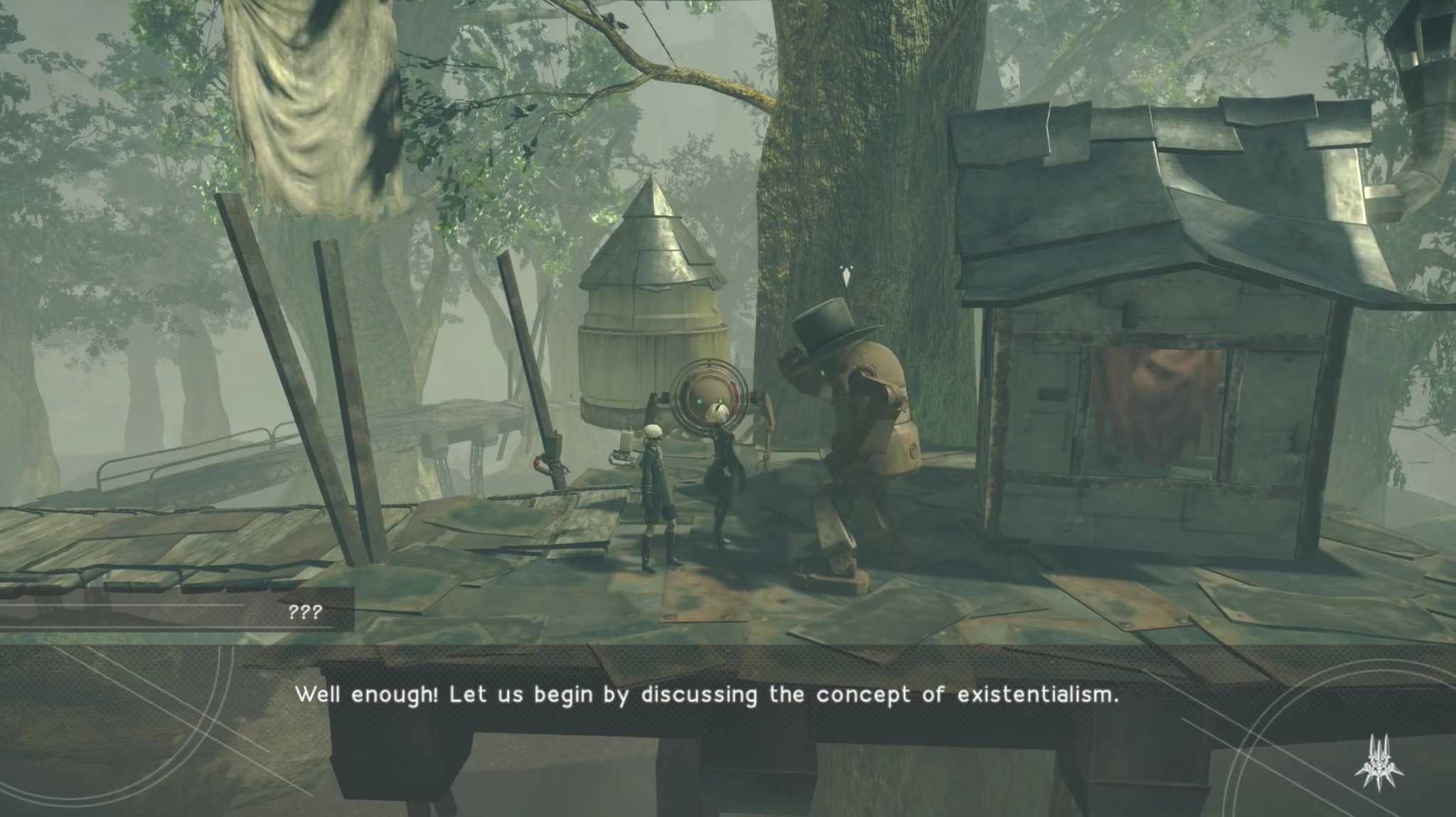

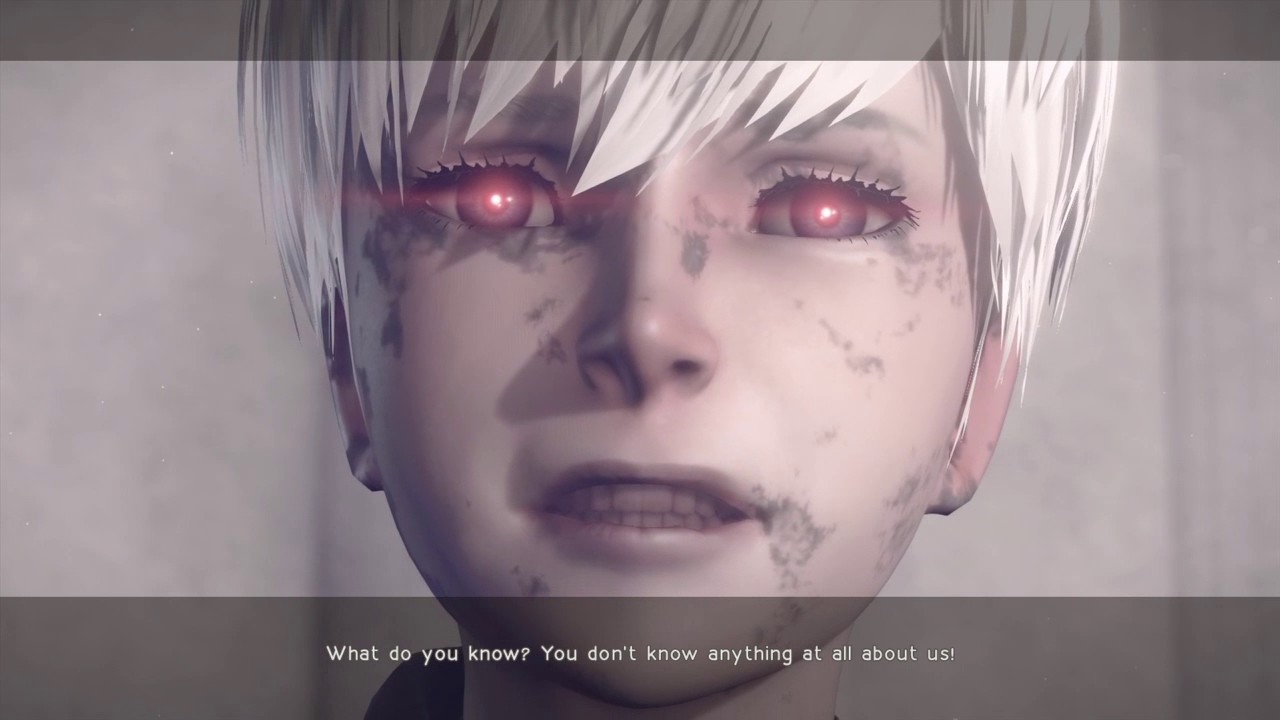

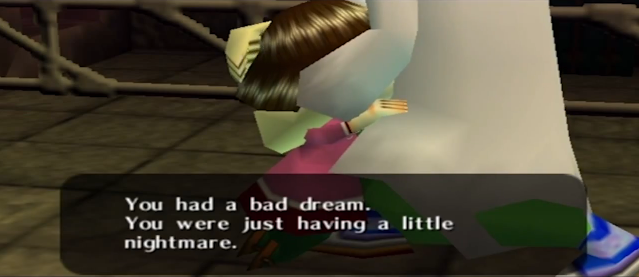

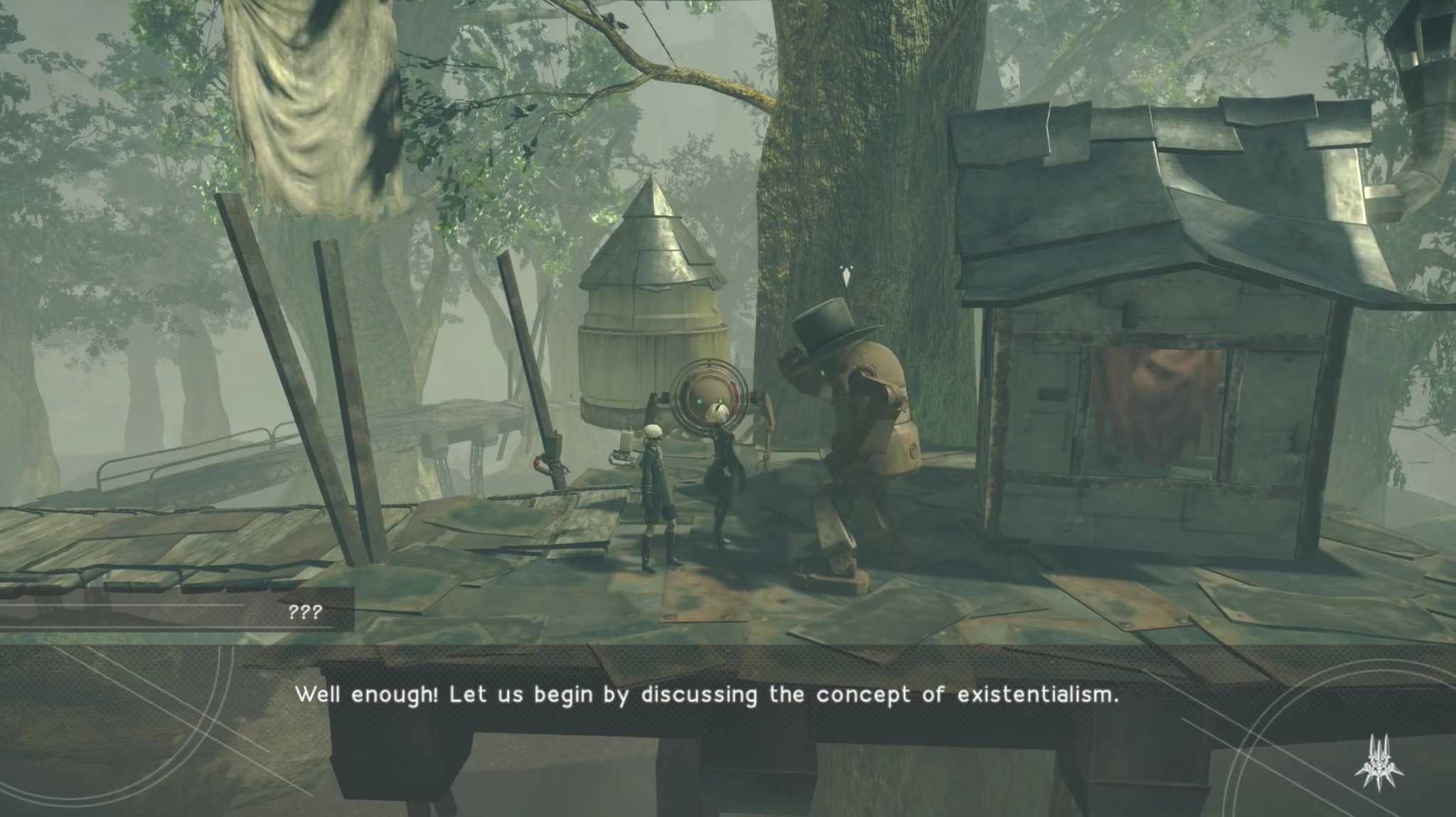

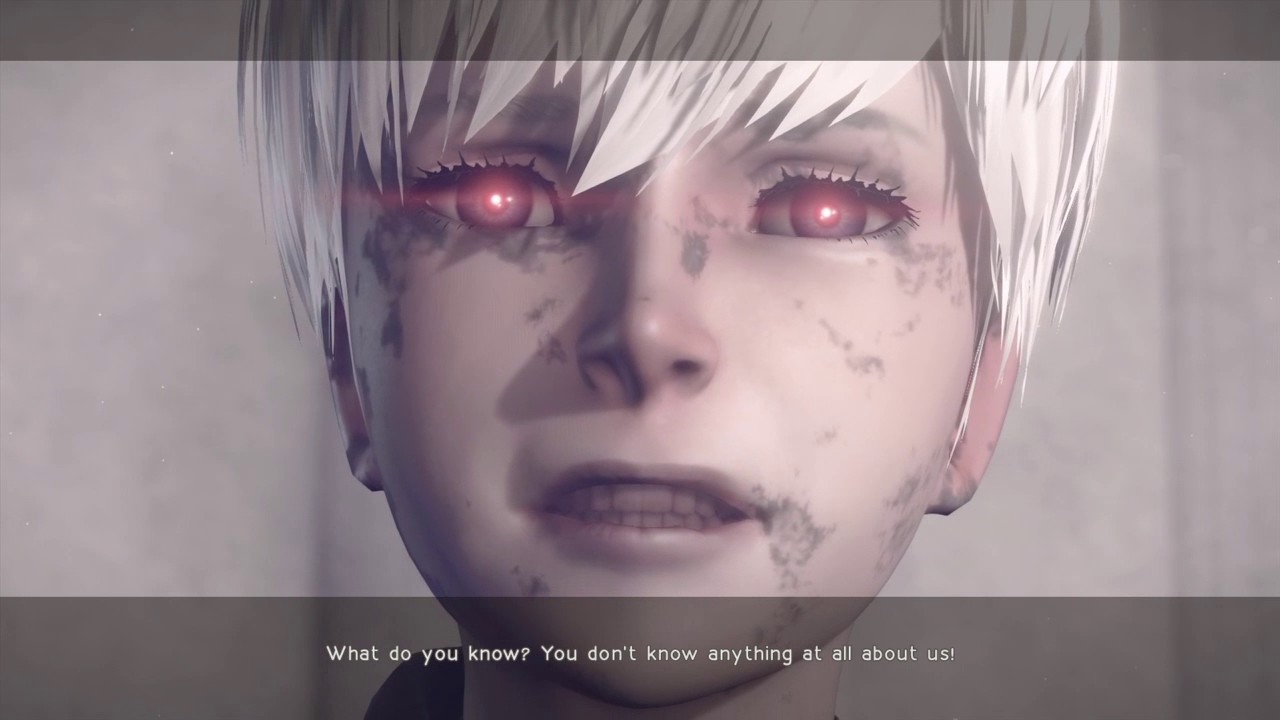

Similar to Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” these robots have lived close-minded lives where they could only imitate what they saw in humanity’s past. However, the

fact that these robots understandably suffer for imitating humanity leads the player to question whether humanity is worth imitating at all even though we believe

we are the pinnacle of civilized thought and behavior in the universe. The android 9S compensates for his loss of purpose after mankind’s extinction by vowing to

protect his comrade 2B. Yet, even this is taken away from him when she is killed in action, and he proceeds on a reckless rampage to destroy every machine on Earth

in retaliation. He ends up exhibiting self-destructive behaviors as he refuses to listen to reason and his body is slowly destroyed, but these events are where he

shows his most human qualities. His blind rage towards the machines because of the loss of his beloved partner are all too similar to the loss of reality we feel

during a breakup or when a loved one in our family dies. Every step from that point becomes a struggle; 9S witnesses illusions of his dead partner and slowly

descends into utter madness, and the player loses combat abilities as 9S’s physical and mental health decays. This all results in a somber, but satisfying experience

where you truly embody the character and share the joys and pains of his journey every step of the way. This kind of intense and emotional storytelling is only

possible through a digital interactive medium, and NieR’s fusion of combat and narrative executes this very well.

Similar to Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” these robots have lived close-minded lives where they could only imitate what they saw in humanity’s past. However, the

fact that these robots understandably suffer for imitating humanity leads the player to question whether humanity is worth imitating at all even though we believe

we are the pinnacle of civilized thought and behavior in the universe. The android 9S compensates for his loss of purpose after mankind’s extinction by vowing to

protect his comrade 2B. Yet, even this is taken away from him when she is killed in action, and he proceeds on a reckless rampage to destroy every machine on Earth

in retaliation. He ends up exhibiting self-destructive behaviors as he refuses to listen to reason and his body is slowly destroyed, but these events are where he

shows his most human qualities. His blind rage towards the machines because of the loss of his beloved partner are all too similar to the loss of reality we feel

during a breakup or when a loved one in our family dies. Every step from that point becomes a struggle; 9S witnesses illusions of his dead partner and slowly

descends into utter madness, and the player loses combat abilities as 9S’s physical and mental health decays. This all results in a somber, but satisfying experience

where you truly embody the character and share the joys and pains of his journey every step of the way. This kind of intense and emotional storytelling is only

possible through a digital interactive medium, and NieR’s fusion of combat and narrative executes this very well.

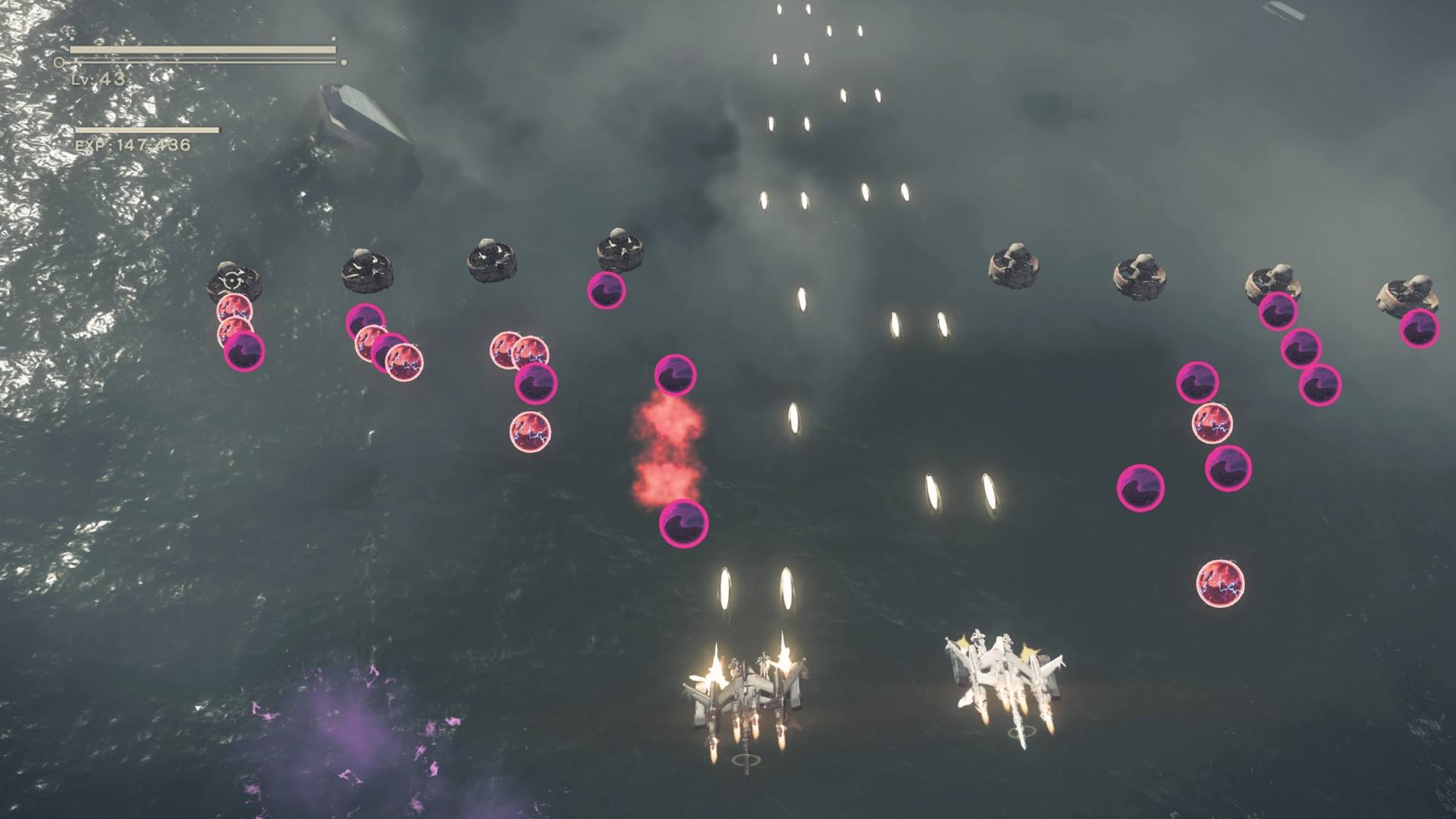

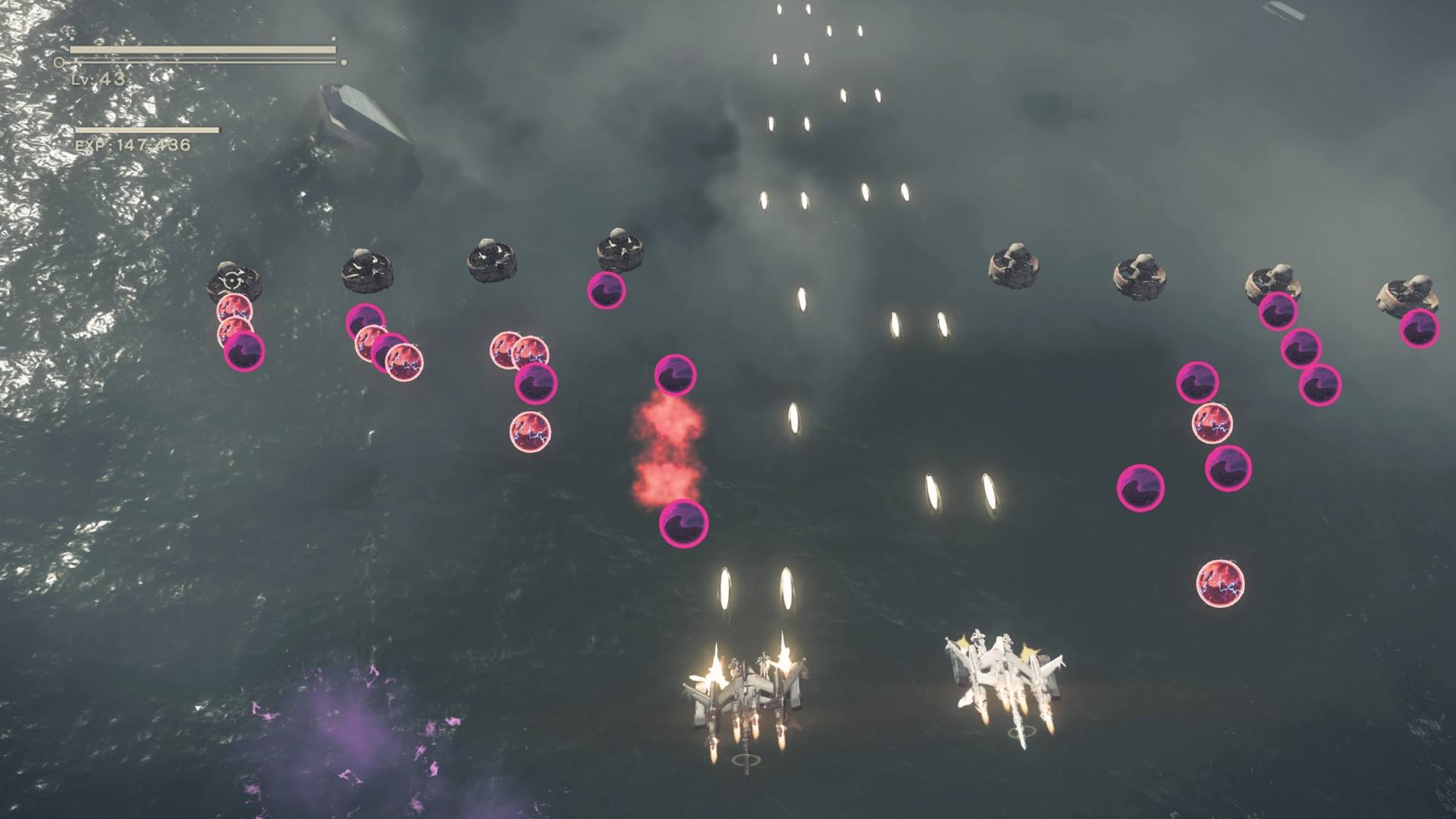

Not every mechanic in NieR is entirely enjoyable, but the immersion to the game that their combination brings creates a compelling experience unlike any other. The

combat and RPG mechanics allow you to easily slip into the belief that you are truly the character on-screen with more choices and consequences than you could ever

imagine. Otherwise bleak and unimaginative levels are quickly warped as your perspective changes and the challenges you face keep you engaged in fast-paced encounters.

A complex story and relatable characters that press you to ask more questions than get answers are accompanied by a grand ensemble of music that captures your emotions

every time you hear them. The game’s ending is truly the essence of NieR’s commitment to immersing you in its world. In bullet-hell fashion, you literally shoot the

names and titles you see in the credits to reach the end while you listen to the ending song. These credits shoot back at you though, and will reach a point where

they become too difficult to surpass alone. At this point you can request help from other players who have chosen to sacrifice all their game save data to help you

overcome this obstacle, all the while the music ramps up with a chorus of all the games developers singing in unison. After finally beating the credits and watching

the last cutscene, the game then allows you to sacrifice your own save data if you wish to help another player beat the credits.

Not every mechanic in NieR is entirely enjoyable, but the immersion to the game that their combination brings creates a compelling experience unlike any other. The

combat and RPG mechanics allow you to easily slip into the belief that you are truly the character on-screen with more choices and consequences than you could ever

imagine. Otherwise bleak and unimaginative levels are quickly warped as your perspective changes and the challenges you face keep you engaged in fast-paced encounters.

A complex story and relatable characters that press you to ask more questions than get answers are accompanied by a grand ensemble of music that captures your emotions

every time you hear them. The game’s ending is truly the essence of NieR’s commitment to immersing you in its world. In bullet-hell fashion, you literally shoot the

names and titles you see in the credits to reach the end while you listen to the ending song. These credits shoot back at you though, and will reach a point where

they become too difficult to surpass alone. At this point you can request help from other players who have chosen to sacrifice all their game save data to help you

overcome this obstacle, all the while the music ramps up with a chorus of all the games developers singing in unison. After finally beating the credits and watching

the last cutscene, the game then allows you to sacrifice your own save data if you wish to help another player beat the credits.

I have never played a game like NieR that has so successfully broken the fourth wall, asked such a great sacrifice of the player, and gifted them with such a heartfelt

reward. What is truly amazing is that this applies not only to the credits, but to the entirety of your game experience, and I believe that is an amazing power that

only digital narratives like NieR are able to provide. NieR: Automata, if nothing else, is an experience unlike any other. All of the interwoven mechanics in the game

distinguish it from the action-adventure genre entirely to create a must-play experience for this generation.

I have never played a game like NieR that has so successfully broken the fourth wall, asked such a great sacrifice of the player, and gifted them with such a heartfelt

reward. What is truly amazing is that this applies not only to the credits, but to the entirety of your game experience, and I believe that is an amazing power that

only digital narratives like NieR are able to provide. NieR: Automata, if nothing else, is an experience unlike any other. All of the interwoven mechanics in the game

distinguish it from the action-adventure genre entirely to create a must-play experience for this generation.

Breath of the Wild - A Wasteland of Potential

Posted 09/26/2020

Nintendo is no stranger to reinventing the formula when developing their flagship titles. Most of their brands usually add 1 or 2 innovative mechanics for their next

mainline games that change up the experience just enough to differentiate it, while still maintaining the core of the experience that fans know and love.Look no

further than games like Super Mario Odyssey, Pokemon Sword/Shield, and Luigi’s Mansion 3 to see what I’m talking about. But what happens when Nintendo takes

“reinventing the formula” to the extremes and completely flips how we think and play a game?

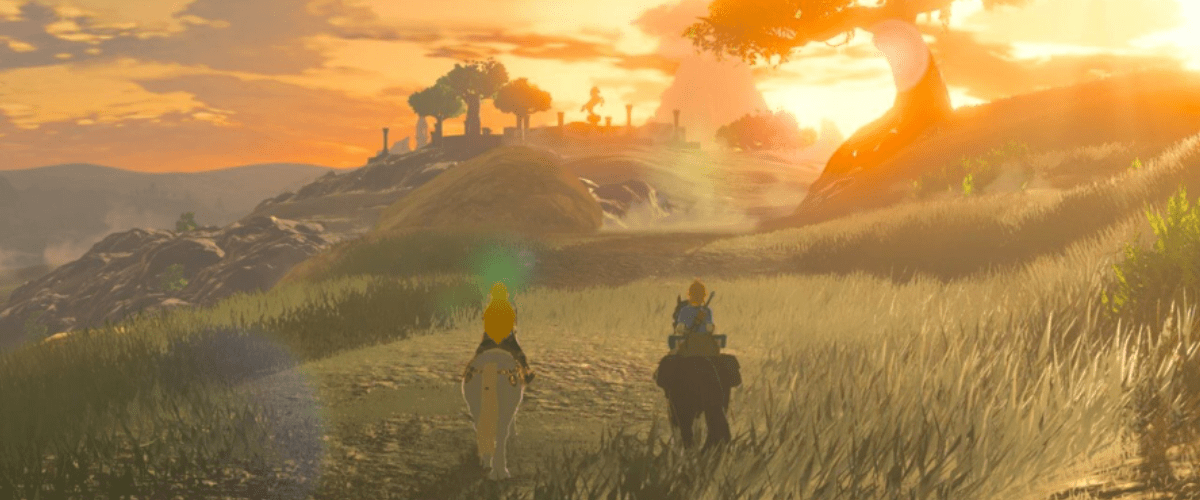

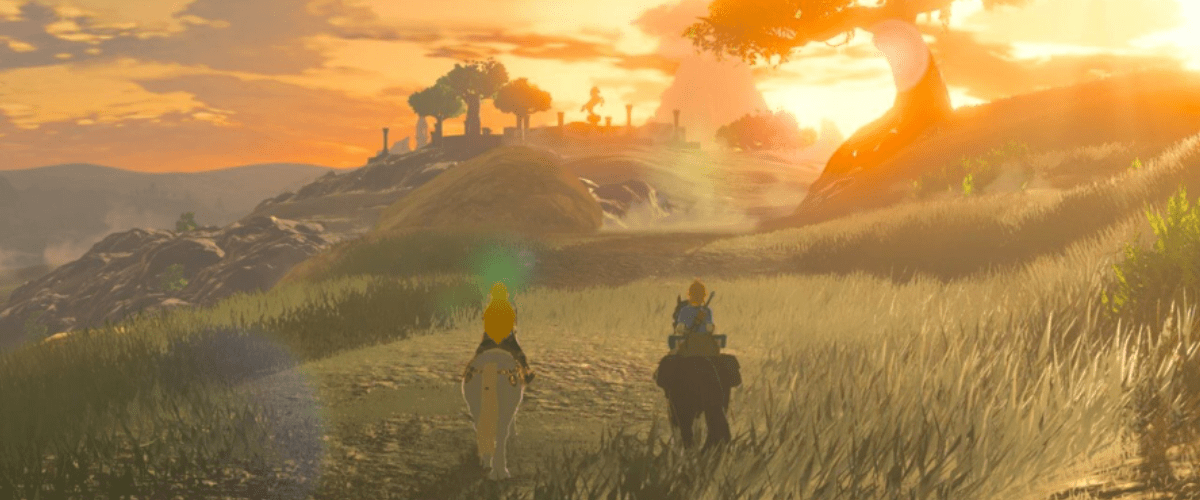

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild was a game changer when it released in 2017 for the Wii U and as a launch title for the Nintendo Switch. Players and critics

alike were drawn into a breathtaking world of possibilities where play centered around using your tools and the environment to save Hyrule by any method you wished.

Gone are the days of traditional Zelda narrative structure where Link progresses through dungeons to acquire key items to eventually defeat Ganon. Now, the player

defines their own adventure and how they’ll be the hero of the story. With such a drastic shift in tempo and structure, Breath of the Wild can be considered an

outsider in comparison to its more linear predecessors. This shift is both a welcome boon for player autonomy and a narrative shortfall for the legacy Zelda has

established over the years.

Let me preface my thoughts by saying that I’ve played nearly every Zelda game to date including Breath of the Wild. My favorites by far are Majoras Mask and Wind

Waker. I'm going into this piece with rose-tinted glasses looking back fondly on my memories of older Zelda games and how Breath of the Wild has changed

everything for better or for worse. Still, it’s important to subjectively look at this game from both the perspective of a series veteran and a newcomer if we are to

understand how Breath of the Wild breaks the mold to its credit and its detriment.

First, let’s examine the level of player autonomy that Breath of the Wild offers. This aspect is mostly a boon to the game and can be considered a positive for

veterans and newcomers. Immediately upon leaving the shrine in the game’s opening moments, the player is greeted with the vast open world of Hyrule. A sensory

overload envelops you: the smoke spiraling from Death Mountain, the lush green of the fields, derelict buildings dotting the landscape, and the chaotic miasma engulfing

Hyrule Castle at the center of everything. Other than a few subtle hints at their goal of saving Hyrule, the player is left entirely to their own devices to explore

the world as they wish. Nothing is off limits as you experiment with everything at your disposal, from cutting down trees to get firewood, to pushing rocks off

cliffs to ambush monsters, and even scaling massive cliffs to devise your own shortcuts. Breath of the Wild introduces players to a world of semi-realism where

if you have a plausible idea, you can probably achieve it in-game. For newcomers, this is an easy concept to adjust to where experimentation is natural from the

start and new ideas are constantly tested. For veterans, this concept takes a bit more effort to get used to. You’re used to relatively static worlds where the

environment around you doesn’t change and there’s usually a specific method of accomplishing a given task. Still, this freedom is a welcome change in giving the

player every possible advantage they could ask for and limiting them only by their creativity.

First, let’s examine the level of player autonomy that Breath of the Wild offers. This aspect is mostly a boon to the game and can be considered a positive for

veterans and newcomers. Immediately upon leaving the shrine in the game’s opening moments, the player is greeted with the vast open world of Hyrule. A sensory

overload envelops you: the smoke spiraling from Death Mountain, the lush green of the fields, derelict buildings dotting the landscape, and the chaotic miasma engulfing

Hyrule Castle at the center of everything. Other than a few subtle hints at their goal of saving Hyrule, the player is left entirely to their own devices to explore

the world as they wish. Nothing is off limits as you experiment with everything at your disposal, from cutting down trees to get firewood, to pushing rocks off

cliffs to ambush monsters, and even scaling massive cliffs to devise your own shortcuts. Breath of the Wild introduces players to a world of semi-realism where

if you have a plausible idea, you can probably achieve it in-game. For newcomers, this is an easy concept to adjust to where experimentation is natural from the

start and new ideas are constantly tested. For veterans, this concept takes a bit more effort to get used to. You’re used to relatively static worlds where the

environment around you doesn’t change and there’s usually a specific method of accomplishing a given task. Still, this freedom is a welcome change in giving the

player every possible advantage they could ask for and limiting them only by their creativity.

If we look at how the narrative structure of Breath of the Wild plays into this, we can see the cracks in the armor more clearly. Aside from the brief tutorial at

the start, the player may travel anywhere on the map and accomplish any task they set their mind to. Speaking with Impa in Kakariko Village (if you choose to even

do this), you’re told that Calamity Ganon ravaged the world 100 years ago and has been contained in Hyrule Castle by Princess Zelda. You were put into a deep sleep

to recover from the wounds you sustained during the battle and have awakened to a world overtaken by nature as the remnants of civilization slowly rebuild

throughout the land. Impa tells you that in order to have the best chance of defeating Ganon, you must travel to the four corners of the world and reclaim the power

of the four divine beasts to weaken Ganon. The key here is that this is completely optional. The player does not have to travel to any of the divine beasts if they

don’t want to, and can even challenge Ganon right from the start if they’re brave enough. From the perspective of player agency, this is a great feature. From a

narrative standpoint, this is where Breath of the Wild suffers the most.

In a game where the player can choose to tackle objectives in any order they wish, it is extremely difficult to formulate a connected story. Linear games are

crafted with the purpose of writers immersing the player in a story that they have crafted down to the very last detail. Some games may give you a bit of freedom

in how you approach missions, but otherwise you are experiencing the story the writers want you to. In this way, they know the exact trials and tribulations that

have led you to every moment and they can connect characters and events to create impactful scenes that form a cohesive narrative. This element is lost to the writer

when the player is let loose to do what they want whenever they like. How do you tie together past events in meaningful dialogue between characters when you have no

idea what the player has experienced? Sure you can do checks to see if they’ve accomplished certain tasks, but this can get pretty complicated depending on how

in-depth you want to go. Characters will engage with the player the same regardless of how ill or well equipped they are or how much of Hyrule they’ve explored.

The Zora telling me about Hyrule’s past means nothing to me when the Goron I spoke with five hours ago gave me the same song and dance. The gravity of the situation

is lost to me when the king of Hyrule’s ghost is watching me charge towards Ganon with a twig and a piece of tape.

In a game where the player can choose to tackle objectives in any order they wish, it is extremely difficult to formulate a connected story. Linear games are

crafted with the purpose of writers immersing the player in a story that they have crafted down to the very last detail. Some games may give you a bit of freedom

in how you approach missions, but otherwise you are experiencing the story the writers want you to. In this way, they know the exact trials and tribulations that

have led you to every moment and they can connect characters and events to create impactful scenes that form a cohesive narrative. This element is lost to the writer

when the player is let loose to do what they want whenever they like. How do you tie together past events in meaningful dialogue between characters when you have no

idea what the player has experienced? Sure you can do checks to see if they’ve accomplished certain tasks, but this can get pretty complicated depending on how

in-depth you want to go. Characters will engage with the player the same regardless of how ill or well equipped they are or how much of Hyrule they’ve explored.

The Zora telling me about Hyrule’s past means nothing to me when the Goron I spoke with five hours ago gave me the same song and dance. The gravity of the situation

is lost to me when the king of Hyrule’s ghost is watching me charge towards Ganon with a twig and a piece of tape.

Breath of the Wild’s unorthodox narrative structure seeps into the environmental storytelling as well. I can appreciate the vast open world and the amount of freedom

that grants me to explore, but it becomes an issue when there’s simultaneously too much and not enough to do. While the divine beasts act as the four main dungeons

of the game before the fight with Ganon, shrines scattered throughout the map make up the vast majority of side quests throughout the game. Each shrine presents a

series of challenges to overcome ranging from solving trigger mechanisms for doors, to gliding across narrow gaps with precise timing, to defeating powerful

guardians. Completing shrines nets you spirit orbs which grant you either increased stamina or health. The shrines are fun activities on their own as you can

expect a new challenge each time you enter one, but the problem lies in the number of shrines and their lack of thematic diversity.

Let’s look at Majora’s Mask to understand what I’m alluding to. The game is fairly shorter than most other Zelda titles with only four mainline dungeons compared

to the dozen or so one would usually get. What Majora’s Mask lacks in quantity, it makes up tenfold in quality. The world of Termina is an alternate reality of

Hyrule where familiar characters and races from Ocarina of Time are turned on their head and given completely new names and roles in the world. The Skull Kid is

using the titular Majora’s Mask to wreak havoc in the world, and his greatest prank involves crashing the moon into Termina in three days' time. Each dungeon lies

in an area with its own populace that’s handling the moon crashing differently. The mayor of Clock Town worriedly listens as the town guard clashes with the

carpenters on whether to evacuate or hold a carnival as scheduled. The Deku King struggles to grasp the reality of the situation as the swamp’s water has been

poisoned and his daughter kidnapped. The Gorons can do naught but remain indoors as a crippling blizzard casts Snowhead Mountain into a neverending hibernation. A

girl weeps for her cursed father in the depths of Ikana Canyon, the land of an ancient kingdom now inhabited by zombies and ghosts who believe the wars of old

never ended. Each area represents a unique challenge to overcome with various side quests to undertake that all link to the central plot of saving as many people

as you can in just three days, even if you must go back in time again and again to reach a happy ending for these people.

Let’s look at Majora’s Mask to understand what I’m alluding to. The game is fairly shorter than most other Zelda titles with only four mainline dungeons compared

to the dozen or so one would usually get. What Majora’s Mask lacks in quantity, it makes up tenfold in quality. The world of Termina is an alternate reality of

Hyrule where familiar characters and races from Ocarina of Time are turned on their head and given completely new names and roles in the world. The Skull Kid is

using the titular Majora’s Mask to wreak havoc in the world, and his greatest prank involves crashing the moon into Termina in three days' time. Each dungeon lies

in an area with its own populace that’s handling the moon crashing differently. The mayor of Clock Town worriedly listens as the town guard clashes with the

carpenters on whether to evacuate or hold a carnival as scheduled. The Deku King struggles to grasp the reality of the situation as the swamp’s water has been

poisoned and his daughter kidnapped. The Gorons can do naught but remain indoors as a crippling blizzard casts Snowhead Mountain into a neverending hibernation. A

girl weeps for her cursed father in the depths of Ikana Canyon, the land of an ancient kingdom now inhabited by zombies and ghosts who believe the wars of old

never ended. Each area represents a unique challenge to overcome with various side quests to undertake that all link to the central plot of saving as many people

as you can in just three days, even if you must go back in time again and again to reach a happy ending for these people.

Returning to Breath of the Wild, this sense of individuality in the areas and dungeons only goes so far. The divine beasts were all created from ancient Sheikah

Technology and thus have a similar aesthetic to them. Apart from the shape of the beasts and their interior layout, each beast has the same look and feel to it.

One could be placed in a random beast and probably guess incorrectly which one they were in. Even the bosses at the end of these dungeons aren’t special; they’re

just incarnations of Calamity Ganon with an added twist like Water Ganon or Wind Ganon. The dungeons have no real impact on the areas around them and seem like

missed opportunities to create interesting dungeons that naturally fit into the world. The shrines have the exact same aesthetic as the divine beasts and can’t be

differentiated based on where they are on the map. Place a map of Hyrule on a dart board and throw a hundred darts around, give each one a name, and you’ve created

all the shrines in the game. Again, the challenges you face within aren’t the problem. It’s the fact that they don’t have a good reason for existing aside from

being cleverly disguised filler content. You can only do so many shrines before you start thinking that you’re good on health and stamina. Now give me a quarter

of the number of shrines, but each one is a building from Hyrule’s past that’s grounded in lore and rewards you a unique item? Now you have my attention.

Returning to Breath of the Wild, this sense of individuality in the areas and dungeons only goes so far. The divine beasts were all created from ancient Sheikah

Technology and thus have a similar aesthetic to them. Apart from the shape of the beasts and their interior layout, each beast has the same look and feel to it.

One could be placed in a random beast and probably guess incorrectly which one they were in. Even the bosses at the end of these dungeons aren’t special; they’re

just incarnations of Calamity Ganon with an added twist like Water Ganon or Wind Ganon. The dungeons have no real impact on the areas around them and seem like

missed opportunities to create interesting dungeons that naturally fit into the world. The shrines have the exact same aesthetic as the divine beasts and can’t be

differentiated based on where they are on the map. Place a map of Hyrule on a dart board and throw a hundred darts around, give each one a name, and you’ve created

all the shrines in the game. Again, the challenges you face within aren’t the problem. It’s the fact that they don’t have a good reason for existing aside from

being cleverly disguised filler content. You can only do so many shrines before you start thinking that you’re good on health and stamina. Now give me a quarter

of the number of shrines, but each one is a building from Hyrule’s past that’s grounded in lore and rewards you a unique item? Now you have my attention.

This leads me to my final point that Breath of the Wild doesn't spend enough time on it’s lore through gameplay. The player can come across signature landmarks where

they’ll enter a cutscene that explores some of Link’s past 100 years ago before the fall of Hyrule. These cutscenes are interesting enough on their own to explain

a bit how the world worked beforehand, but they don’t do the rich history of Hyrule justice on their own. There are so many aspects of Zelda lore that Breath of

the Wild has rightly included for veterans of the series to see in game. Yet, very few of these are explored with any depth at all. We get masterpieces like the

excitement of exploring a corrupted Hyrule Castle or the trials of navigating the Lost Woods to pull out the legendary Master Sword from its pedestal. We also feel

empty when we come across a ruined Temple of Time, a key building from Ocarina of Time, and there’s nothing to do there but scale its walls and pray. Nothing more

of Lon Lon Ranch remains aside from a few fence posts and a patch of land that was once the horse race track.

This leads me to my final point that Breath of the Wild doesn't spend enough time on it’s lore through gameplay. The player can come across signature landmarks where

they’ll enter a cutscene that explores some of Link’s past 100 years ago before the fall of Hyrule. These cutscenes are interesting enough on their own to explain

a bit how the world worked beforehand, but they don’t do the rich history of Hyrule justice on their own. There are so many aspects of Zelda lore that Breath of

the Wild has rightly included for veterans of the series to see in game. Yet, very few of these are explored with any depth at all. We get masterpieces like the

excitement of exploring a corrupted Hyrule Castle or the trials of navigating the Lost Woods to pull out the legendary Master Sword from its pedestal. We also feel

empty when we come across a ruined Temple of Time, a key building from Ocarina of Time, and there’s nothing to do there but scale its walls and pray. Nothing more

of Lon Lon Ranch remains aside from a few fence posts and a patch of land that was once the horse race track.

Even if we take off our rose-tinted glasses, this is still a problem because there is almost nothing interesting for the player to do with these areas from either

an adventuring or a lore building perspective. Sure a few of the guard posts and villages have chests to find, but it's usually just standard items like arrows or

materials. I can find these same items at a dozen stores around the map. A hundred years have passed since these places were destroyed and now overgrowth has

consumed these once beautiful areas. Any environmental clues to indicate a past were either eroded over time or are so insignificant that they don’t stand out

in a meaningful way. To incorporate all of these landmarks and not provide the player incentive to investigate or enough context to become invested is the true

crime here.

Breath of the Wild is a fascinating case study for me. I loved the game while I played and occasionally still go back to do side content now and then. What

frustrates me is that for just as much as the game changes the Zelda formula in the right ways with player freedom, it also goes in the wrong direction with

its structure and storytelling. That’s why I’m so excited to see how Nintendo handles the sequel to this game. If they stick with the same Hyrule we’ve explored

as a desolate wasteland, perhaps this could be the big turnaround where we see Link and Zelda begin rebuilding a more dynamic world. Instead of reminiscing about

a past you never lived, the player can use the creativity the game grants them to forge their own vision of what Hyrule will become. Whatever the case, you can

count on Nintendo to push the boundaries of adventure once again.

Breath of the Wild is a fascinating case study for me. I loved the game while I played and occasionally still go back to do side content now and then. What

frustrates me is that for just as much as the game changes the Zelda formula in the right ways with player freedom, it also goes in the wrong direction with

its structure and storytelling. That’s why I’m so excited to see how Nintendo handles the sequel to this game. If they stick with the same Hyrule we’ve explored

as a desolate wasteland, perhaps this could be the big turnaround where we see Link and Zelda begin rebuilding a more dynamic world. Instead of reminiscing about

a past you never lived, the player can use the creativity the game grants them to forge their own vision of what Hyrule will become. Whatever the case, you can

count on Nintendo to push the boundaries of adventure once again.

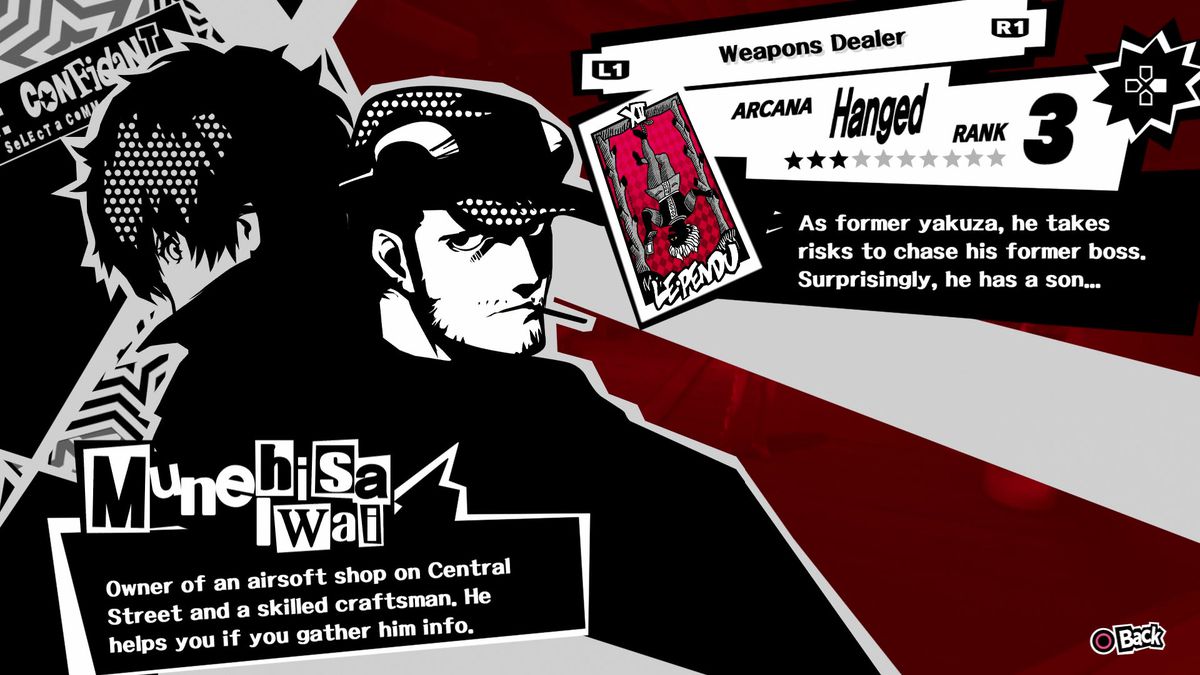

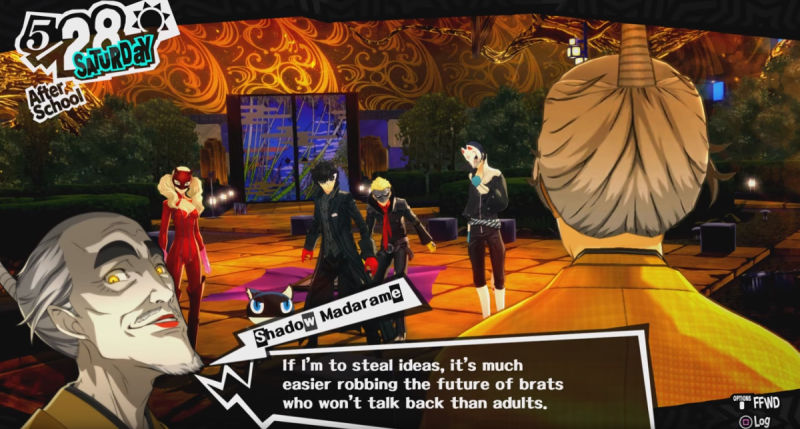

Persona 5 - Embodying the Protagonist

Posted 09/25/2020

What is the primary purpose of an RPG? People may have different answers depending on what they’re looking for in the experience. Some days, you might catch me saying

a good RPG has a huge skill tree with endless customization to fit my exact playstyle. Other days, I would say it must have a solid narrative with engaging characters

that provide you with a variety of quests to undertake in pursuit of some lofty goal that will take you a hundred hours to accomplish. Both of these answers are fine,

but they don’t really define what an RPG is intended to accomplish at its core. It’s pretty simple: an RPG is meant to allow the player to assume the role of their

character.

There are many excellent games that accomplish this level of immersion, and some that truly walk a needle-thin line in separating the player from their

character. Persona 5 was one of my top games of the year when it released in 2017, and it only got better with the various additions added in the Royal version

released this year. While plenty of aspects make Persona 5 a must-play game, the design choices that allow players to embody the game’s

protagonist, Joker, take role-playing to the next level.

To understand how Persona 5 excels with role immersion, we should first take a look at other games, both RPG and non-RPG, that take a crack at it. The biggest

target to look at is The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. Nearly every discussion of RPG’s involves Bethesda’s nordic-fantasy adventure, so we’ll start there. In Skyrim,

you start by customizing your character as much or as little as you like. From there you’re thrown into a chaotic escape sequence to avoid a dragon as well as your

own execution. Along the way, you get tutorials of the basics like combat, your inventory, the skill system, etc. Finally, you reach “the point,” which is typical

in open-world games like this. This “point” is where the game allows the player near absolute freedom to do whatever and go wherever they want. You write your head

canon for what your past was like and act out how you’re going to either be a part of the world you’ve entered, or how you’re going to abuse it to your advantage.

Skyrim does not railroad the player into doing anything they don’t want to do, and this can hurt the game’s role immersion. I’m not saying that the freedom in Skyrim

is a poor design choice, but I am saying that the loose reins allows players to easily disconnect from their role in the world. Of course, one can argue that this

is contradictory since I just said the player decides their own role.

To understand how Persona 5 excels with role immersion, we should first take a look at other games, both RPG and non-RPG, that take a crack at it. The biggest

target to look at is The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. Nearly every discussion of RPG’s involves Bethesda’s nordic-fantasy adventure, so we’ll start there. In Skyrim,

you start by customizing your character as much or as little as you like. From there you’re thrown into a chaotic escape sequence to avoid a dragon as well as your

own execution. Along the way, you get tutorials of the basics like combat, your inventory, the skill system, etc. Finally, you reach “the point,” which is typical

in open-world games like this. This “point” is where the game allows the player near absolute freedom to do whatever and go wherever they want. You write your head

canon for what your past was like and act out how you’re going to either be a part of the world you’ve entered, or how you’re going to abuse it to your advantage.

Skyrim does not railroad the player into doing anything they don’t want to do, and this can hurt the game’s role immersion. I’m not saying that the freedom in Skyrim

is a poor design choice, but I am saying that the loose reins allows players to easily disconnect from their role in the world. Of course, one can argue that this

is contradictory since I just said the player decides their own role.

Consider the thought that Skyrim can be played not as a game, but as a simulator of

sorts for a character thrust into this world under unfavorable circumstances. You can play the game in a “realistic” manner where you adhere to the main storyline

while doing side quests and steadily gaining power, prestige, and coin to reach an end to your journey (if you choose to end it that is). In this way, you’ve

embodied the role of the Dovakhin just as the game implies you do and you reach that point of role immersion to an extent. However, say you choose to play Skyrim

as a game. You understand the level of freedom you’re given and take advantage of this by shrugging off the story and becoming the best damn blacksmith in the world.

Congratulations, you’ve just reached max smithing level. Now you want to sell your wares and make a fortune. Gotta have a mansion to go with it as well, right?

Now you’re bored. Why don’t you take one of your godly weapons and test it out on some NPCs in town? Guess they didn’t like that, so they chased you out of town.

That's ok, though, because you walk back in after waiting a day and everyone forgot you're a psychopathic murderer. The best part about all of this? It’s a totally

acceptable playstyle. Yet, it’s because of your freedom to go off the rails like this that you probably won’t feel immersed in yourself as a character in this

world. What kind of a structured world would allow you to get away with insane feats without consequences? You partake in actions, not to express yourself as an

inhabitant of this world, but because you want to do it and nothing’s stopping you. Murder Hobo is a good term for this that’s used frequently in Dungeons and

Dragons where players aren’t adapting their playstyle or mannerisms to the character and backstory they’ve created, but instead just doing stuff because they

want to and they can.

Let’s look at a non-traditional example: Halo. Halo is not an RPG from the widely recognized perspective of having quest systems, character customization, leveling,

or anything like this. But if we look at RPGs as having role immersion at the core of the experience, then Halo can be considered an RPG. There are many games in the

series, but we’ll condense them for now into the very first Halo game. The game starts off with the alien Covenant fleet pursuing the Pillar of Autumn ship outside

of orbit of a massive halo ring. All signs indicate that this is a losing battle for the humans aboard the Autumn, and the only hope of survival lies in you, the Master

Chief. You wake up from cryosleep as the last supersoldier of your kind and humanity’s only hope in the war against the Covenant. Through a series of fairly linear

missions, you prove your prowess as a Spartan by fending off the Covenant, unraveling the mysteries of the Halo ring, and preventing the complete and utter

annihilation of the galaxy. I have just told you the story of the Master Chief, and to be honest pretty much every Halo game to date. Where Halo fails to give you

creative dialogue to express yourself, Chief’s got a memorable one-liner to punctuate the mood. When Halo lacks the opportunity to explore the environment and tread

off the beaten path, Cortana reminds you of the gravity of your situation and steers you back towards the action. The Master Chief is always the focus of the story

and he’s forever at the center of the fight. In this way, he’s become a true legend of his world.

Let’s look at a non-traditional example: Halo. Halo is not an RPG from the widely recognized perspective of having quest systems, character customization, leveling,

or anything like this. But if we look at RPGs as having role immersion at the core of the experience, then Halo can be considered an RPG. There are many games in the

series, but we’ll condense them for now into the very first Halo game. The game starts off with the alien Covenant fleet pursuing the Pillar of Autumn ship outside

of orbit of a massive halo ring. All signs indicate that this is a losing battle for the humans aboard the Autumn, and the only hope of survival lies in you, the Master

Chief. You wake up from cryosleep as the last supersoldier of your kind and humanity’s only hope in the war against the Covenant. Through a series of fairly linear

missions, you prove your prowess as a Spartan by fending off the Covenant, unraveling the mysteries of the Halo ring, and preventing the complete and utter

annihilation of the galaxy. I have just told you the story of the Master Chief, and to be honest pretty much every Halo game to date. Where Halo fails to give you

creative dialogue to express yourself, Chief’s got a memorable one-liner to punctuate the mood. When Halo lacks the opportunity to explore the environment and tread

off the beaten path, Cortana reminds you of the gravity of your situation and steers you back towards the action. The Master Chief is always the focus of the story

and he’s forever at the center of the fight. In this way, he’s become a true legend of his world.

Yet, it is this same legend of the Master Chief that isolates him

from the player. While Skyrim gave the player far too much freedom, Halo manages to restrict the player from really identifying as the Master Chief. Characters in

the game will never refer to you, the player, but instead to Chief. In kind, Chief will respond with the same line he’s been programmed to give. No matter how

fantastic the words or their delivery will be, these are not your words. They are the words written in the sci-fi space odyssey that is the legend of the Master

Chief. His story has already been written, and you are the tool that will relive his saga time and time again. This is not to say I hate this aspect of Halo.

It serves as an engaging form of storytelling that attempts to blur the line between player and character. Yet, it can only go so far in granting the player the level

of depth they may want from assuming the role of the Chief while maintaining some aspect of themselves. We all like to think that our face lies underneath Chief’s

helmet, but we don’t have to worry about that. His visor always reflects what’s ahead of him, and that’s his next epic battle.

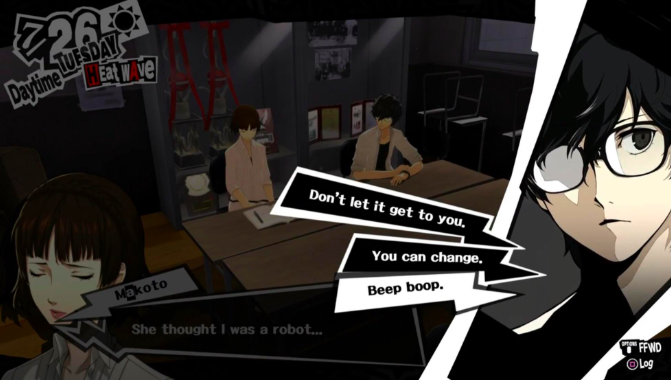

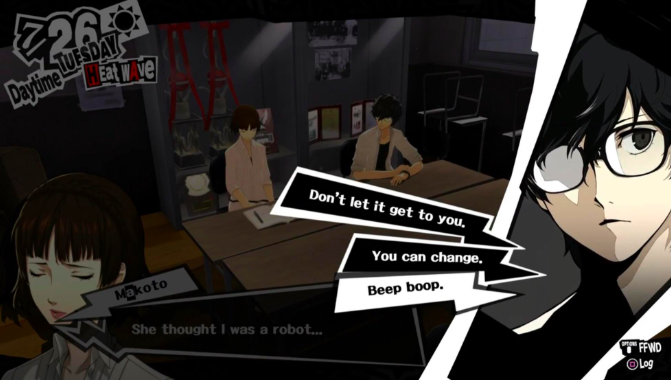

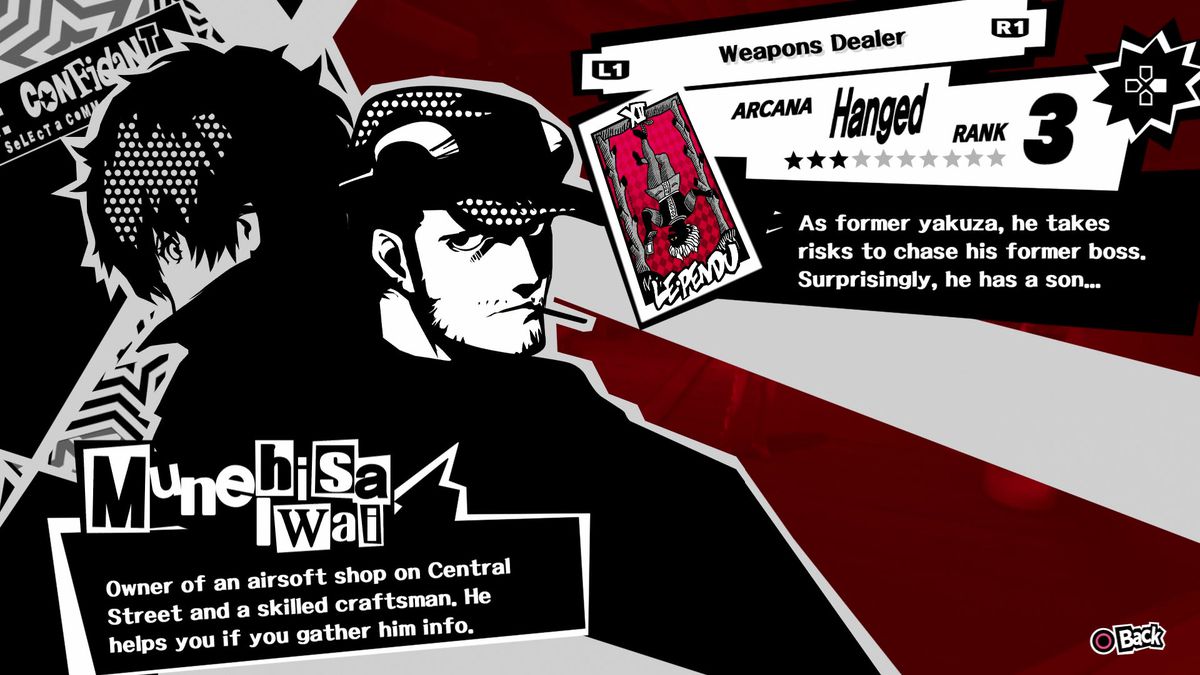

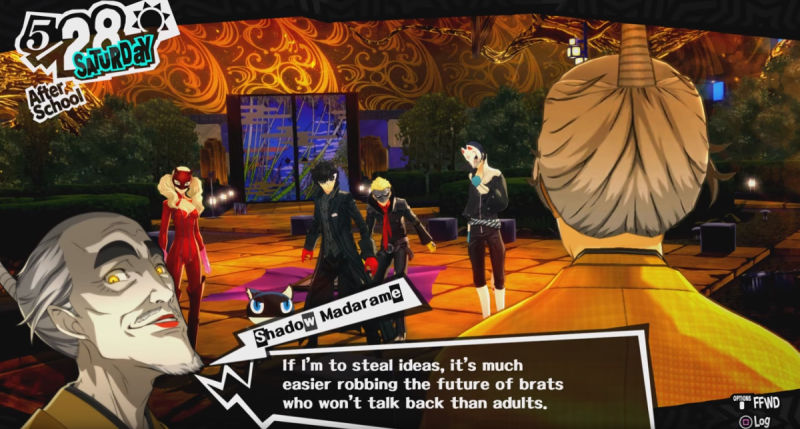

We’ve examined both the king of RPG’s and the king of shooters. Let’s see how Persona 5 mixes up the formula to create something truly special. You play as the

Protagonist (or Joker a bit later in the game) living in modern-day Tokyo. You aren’t on some grand quest to slay an all-powerful dragon, or even part of an epic

battle to save the world. Nope. You are an average high-school student who studies for exams, hangs out with friends after class, makes minimum wage at the nearby

beef bowl shop, and goes to sleep every night in the attic of an old-fashioned coffee shop. This is the new standard for fun in gaming and you will like it. In all

seriousness though, it doesn’t necessarily seem like the kind of setting and plot that would get anyone hyped up to play this game immediately. This is where looks

are deceiving, and it all ties into the main theme of the game. Joker starts the game under probation as he’s been framed for a crime he didn’t commit. Your goal

starts off simple with attending a new school and trying not to cause problems as you’ve already been branded a troublemaker by students and teachers. It’s a shame

though when you realize you’re not the only one feeling the pressures of society and the unrealistic demands of the adults around you. You become friends with other